2.1 Ancient Ideas of Atomism & Plenism

The "Waves or Particles" Debate Goes Back to Ancient Greece

Little is known of Leucippus, the 5th century BC Greek philosopher credited as the originator of atomism. A millennium later, the Byzantine philosopher Simplicius of Cilicia (~AD 490–~560) described Leucippus’ ideas:

[H]e held that being no more exists than non-being, and both are equally causes of the things that come into being. For supposing that the substance of the atoms is solid and full, he said that it was being and that it was carried about in the void, which he called non-being and which he says exists no less than being [[i]].

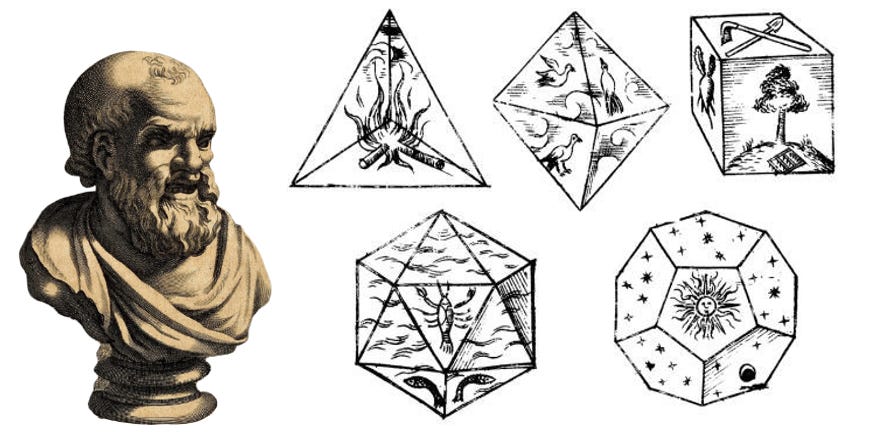

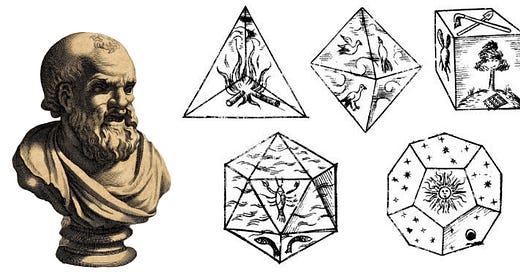

Similarly little is known of Leucippus’ supposed student and successor, Democritus (~460–~370 BC). In Timaeus, Plato associated each of five elements – fire, air, earth, water, and æther – with a regular solid: tetrahedron, octahedron, cube, isocahedron, and dodecahedron. Figure 2.3 shows Democritus as well as a diagram by Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) of Plato’s interpretation of Democritus’ atomic theory.

Democritus’ thinking appears to have been more complicated and subtle, however. In a lost essay from which only fragments remain, Aristotle describes Democritus’ own atomic model of reality:

Democritus thinks that the nature of eternal things consists in small substances, infinite in quantity, and for them he posits a place, distinct from them and infinite in extent. He calls place by the names ‘void,’ ‘nothing,’ and ‘infinite’; and each of the substances he calls ‘thing,’ ‘solid,’ and ‘being.’ He thinks that the substances are so small that they escape our senses, and that they possess all sorts of forms and all sorts of shapes and differences in magnitude… [[iv]]

The Greek physician, Galen of Pergamon (AD 129–210), reported Democritus indicted the senses, saying:

By convention color, by convention sweet, by convention bitter: in reality atoms and void [[v]].

Galen also reports Democritus noted the contradiction inherent in arguing against the validity of perception while employing that same method:

Poor mind, do you take your evidence from us and then try to overthrow us? Our overthrow is your fall [[vi]].

Democritus observed that the senses fail to provide a full and complete picture of reality, yet he also apparently recognized that it was through the senses that we acquire what knowledge we can about how reality works.

Democritus’ atomism influenced Epicurus (341–270 BC). Where Democritus thought reality unfolded according to the purely deterministic actions of atoms interacting in a void, Epicurus held that occasionally atoms randomly “swerve.” This, in his view, was the physical basis of free will.

The Roman poet and philosopher, Lucretius (~99–~55 BC), wrote, On the Nature of Things, elaborating upon the ideas of Democritus and Epicurus. Lucretius extended upon the Epicurean swerve, describing a curious random spontaneous movement of small dust particles:

Observe what happens when sunbeams are admitted into a building and shed light on its shadowy places. You will see a multitude of tiny particles mingling in a multitude of ways... their dancing is an actual indication of underlying movements of matter that are hidden from our sight... It originates with the atoms which move of themselves. Then those small compound bodies that are least removed from the impetus of the atoms are set in motion by the impact of their invisible blows and in turn cannon against slightly larger bodies. So the movement mounts up from the atoms and gradually emerges to the level of our senses so that those bodies are in motion that we see in sunbeams, moved by blows that remain invisible [[vii]].

When rediscovered circa AD 1415, Lucretius’ ideas inspired atomic and corpuscular doctrines of nature.

In 1827, the Scottish botanist, Robert Brown (1773–1858) microscopically examined pollen from “pinkfairies” (Clarkia pulchella), a flower first discovered in northern Idaho by Lewis & Clark in 1806 [[viii]]. Brown noted his pollen particles immersed in water were in constant motion [[ix]]. This became known as “Brownian motion.” In 1905, Albert Einstein (1879–1955) presented a statistical model explaining Lucretius’ observation in terms of atomic theory:

It will be shown in this paper that, according to the molecular-kinetic theory of heat, bodies of microscopically visible size suspended in liquids must, as a result of thermal molecular motions, perform motions of such magnitude that these motions can easily be detected by a microscope [[x]].

Lucretius further observed that clothes hung out near a shore become wet and hung out in the sun become dry, the minute portions of moisture imperceptible to the eye. We can sense odors that we cannot otherwise perceive. Matter exists in small quantities and accumulates or decreases without being seen. Figure 2.4 shows Galen, Epicurus, and Lucretius.

Aristotle opposed this atomistic thinking [[xiv]]. Later philosophers summarized Aristotle’s position, as “nature abhors a vacuum.” In his analysis, Aristotle presented the arguments supporting the existence of a void:

…first, that without such a void, no motion could take place; secondly, the fact of contraction seems to prove the existence of an internal void… the fact of growth proves that nutriment can be added to the same body, which must have an internal void to be filled... [[xv]]

Aristotle countered these arguments from the perspective of reality as a “plenum,” a continuity pervading all space. Figure 2.5 shows Aristotle’s model in a diagram created by the German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716). Matter comprises air and fire (which tended to return to their rightful place, up), and water and earth, (which sought to return down). A subtle fifth element, the æther or “quintessence,” makes up the heavens. All of reality comprises a space occupied by one of these five kinds of matter, in Aristotle’s view.

As something changes location, whatever exists there also moves to make room, Aristotle argued. The rotation of a wheel and vortices in liquid are examples of motion in a continuum. In Aristotle’s view, a true void or nothingness would have no properties or characteristics to enable it to accept or transmit matter or influences. Finally, Aristotle argued, matter may possess the characteristic of being either dense or rare, changing the volume it occupies.

In large part, Aristotle’s criticism of the void relied upon his theory of motion. He classified terrestrial motion as linear and celestial motion as circular. Aristotle argued that all motion would cease unless continually acted upon by some outside agency or cause. The velocity depends upon the ratio of the force to the resistance offered. An isolated atom in a void would have nothing to push it in any particular direction – neither force nor resistance. Logically then, an atom could not possibly move.

Such was the power of Aristotle’s writing and the respect with which he was held that Aristotle’s physics, including his views on motion, and the plenum, would dominate physical thought until the Renaissance.

Next time, 2.2 Early and Medieval Physics

You may follow me online in other places as well:

Telegram: 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕔𝕫𝕒𝕣'𝕤 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕥𝕣𝕖𝕒𝕞

Gab: @aetherczar

Twitter: @aetherczar

Amazon: Hans G. Schantz

[i] Simplicius, Commentary on the Physics 28.4-15, as cited by Barnes, Jonathan, Early Greek Philosophy, London: Penguin Books, 1987, p. 243.

[ii] Kepler, J. (1619). Harmonices mundi libri, V. Gottfried Tampach Linz.

[iii] Democritus. Line engraving. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY.

[iv] Aristotle, On Democritus, as cited by Barnes, Jonathan, Early Greek Philosophy, London: Penguin Books, 1987, p. 247.

[v] Galen, On Medical Experience XV 7-8, as cited by Barnes, Jonathan, Early Greek Philosophy, London: Penguin Books, 1987, p. 254.

[vi] Ibid. p. 255.

[vii] Lucretius, “On the Nature of Things,” Book II, verses 113-140, ~60BC.

[viii] Lewis, Meriwether, Journal, Entry of Sunday, June 1, 1806. See: https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1806-06-01#lc.jrn.1806-06-01.01

[ix] Brown, R., “A brief account of microscopical observations, made in the months of June, July, and August, 1827 on the particles contained in the pollen of plants; and on the general existence of active molecules in organic and inorganic bodies. Privately printed. Reprinted in Edin. New Phil. J. 1828, 5, 358-371. See: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Miscellaneous_Botanical_Works_of_Rob/_KwUAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=robert%20brown%20brownian%20motion&pg=PA467&printsec=frontcover

[x] Einstein, Albert, “Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen” [On the Movement of Small Particles Suspended in Stationary Liquids Required by the Molecular-Kinetic Theory of Heat]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 322 (8), 1905, pp. 549–560.

[xi] Galen. Line engraving. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY.

[xii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Epicurus_bust2.jpg.

[xiii] The philosopher and poet Lucretius pointing up at the revolving globe of Chance in the sky. Engraving by M. Burghers, ca. 1682, after T. Creech. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY.

[xiv] Aristotle, Physics, iV 6-9, as cited by Barnes, Jonathan, The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, vol. 1, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984, pp. 362-369.

[xv] Randall, John Herman, Aristotle, New York: Columbia University Press, 1960, p. 198. See: https://amzn.to/4aqO2bc

[xvi] Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, Dissertatio de arte combinatoria, in qua ex arithmeticae fundamentis complicationum ac transpositionum doctrina nouis praeceptis exstruitur ... noua etiam Artis meditandis, seu Logicae inuentionis semina sparguntur. Praefixa est synopsis totius tractatus, & additamenti loco demonstratio existentiae Dei, ad mathematicam certitudinem exacta autore Gottfredo Guilielmo Leibnüzio, 1666, p. 18. See: https://archive.org/details/ita-bnc-mag-00000844-001/page/n18/mode/2up.

This is an excellent piece on atomism as well. It covers similar ground: https://www.thecollector.com/ancient-greeks-discover-atoms-atomism/

Those are the only 2 ways of slicing it since forever. 1) Bumping particles 2) Universal aether. I fall into the aether camp, myself.