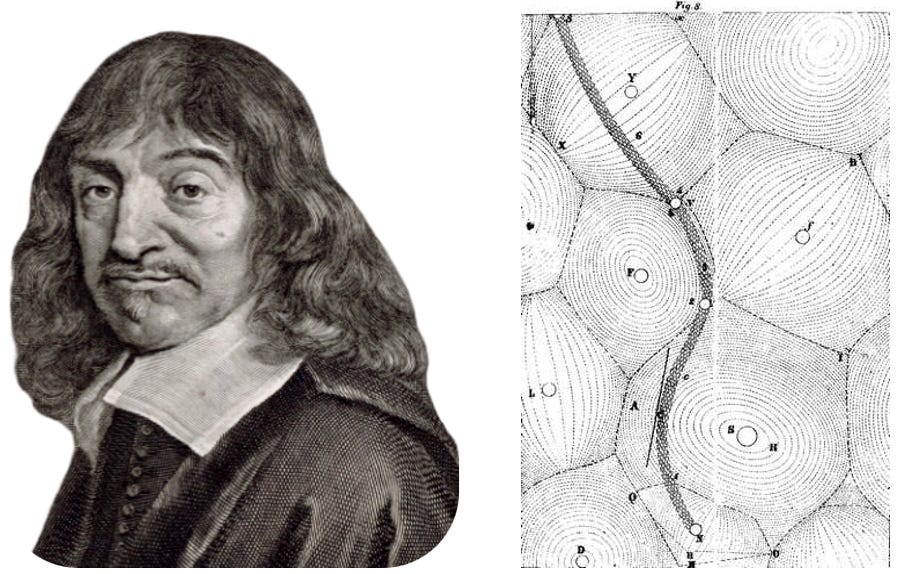

That the victor writes the history is as true for the history of science as it is for military and political history. Students are taught that the evolution of science is a straight progression. They are taught that scientists stack insights and discoveries one on another to yield the conceptual edifice we take for granted today. The actual development is a far messier affair. Some valid insights are overlooked and must be rediscovered by later researchers. Erroneous notions may capture and hold the imaginations of scholars for many decades or even centuries. While Kepler, Galileo, and others were laying the foundation for the discoveries of Isaac Newton (1642–1727), seventeenth century physics fell under the sway of René Descartes (1596–1650). Let’s pause a moment to consider his ideas.

As a young man, Descartes had a vision that all science was interconnected. He reasoned that if only he could find and grasp the fundamental truth, he could discover everything else through deduction. In his Discourse on Method (1637), Descartes makes the claim:

...I showed what were the laws of nature; and without supporting my reasons on any other principle but the infinite perfections of God, I tried to demonstrate all the laws about which one might have been able to doubt and to show that they were such that, even if God had created several worlds, there could have been none in which these laws failed to be observed [[i]].

Like Plato, Descartes held that one could deduce the nature of reality from first principles. For Plato, the “Idea of the Good” was the a priori principle from which all truths could be deduced [[ii]]. For Descartes, the “infinite perfections of God” was the a priori principle from which all the facts of reality could be explained without reference to experience. For Descartes, the fact of consciousness was primary; existence was a secondary consequence. Thus, he took as the first principle of his philosophic system the dictum: “I think, therefore I am” [[iii]].

Descartes sounds Baconian in his proto-transhumanist philosophy [[iv]]. Descartes believed, that, through science, humanity could “render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature,” so as to “enjoy without any trouble the fruits of the earth, and all its comforts,” and that, in particular, medical advances could “render men wiser and more ingenious than hitherto” [[v]].

What of Descartes’ science? In optics, he showed how the refraction of light was explained by assuming that light travels faster in water than in air [[vi]]. His laws of motion included the idea that the total quantity of “motion” was conserved [[vii]]. His principle was similar to what we now hold as the conservation of momentum – the product of mass and velocity in each direction – but for Descartes, “motion” was the product of volume and velocity. Finally, he correctly identified the law of inertia, that a body would tend to move in a straight line until or unless acted on by some agency [[viii]].

In evaluating a scientist’s work, we must distinguish between errors in method on the one hand and conclusions that we recognize to be mistakes based on the superior context of knowledge provided by additional centuries of discoveries on the other hand. How did Descartes do in retrospect? In optics, his contemporary, Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665), mathematically showed that the laws of refraction of light could just as readily be derived by assuming that light travels more slowly in water than in air instead of more quickly [[ix]]. In short, there were two equally valid explanations for refraction. Contrary to Descartes, there is no a priori way of distinguishing between them. It remained for later experiment to judge which view was correct. In 1851 when Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau (1819–1896) and Jean Bernard Léon Foucault (1819–1868) finally measured the speed of light, Fermat’s view was found to be the true explanation [[x]].

As for his laws of motion, Descartes came tantalizingly close, but fell short of the mark. His law of the conservation of motion called for the conservation of the product of volume and velocity, so it would hold true only for interactions between bodies with the same density. Further, he argued that motion was only globally conserved, rather than being conserved “component-wise” in each direction. His errors on these points were noted by Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (1646–1716).

In addition, Descartes held a “corpuscular” view of reality – that all space is full of particles of various kinds whose motions give rise to physical effects. He also attempted to explain the motion of the planets in terms of celestial particles. These swirling particles explained, in his view, why air remains pressed against the surface of the Earth, and why planets orbit the sun, guided by the circular swirls of particles.

His views led Descartes to some prescient insights, for instance, that heat is the rapid motion of the particles that make up material objects. Further to his credit, Descartes was a pioneer in analytic geometry. Every student of algebra is familiar with his “Cartesian axes.” Descartes’ overall performance in physics (amounting to little better than arbitrary speculation) was mediocre. As historian A. Rupert Hall (1920–2009) observed:

The high claim for intuition became, indeed, absurd when only the first of Descartes’ seven rules of collision was found to be correct. Unguarded, unrestricted intuition slipped insensibly into sheer imagination.... And Descartes almost confessed as much when he professed to write not of the universe and men as they are, but as they must be [[xiii]].

Descartes lounged about in bed reading, writing, and thinking deep thoughts, usually rising in time for lunch. While certain of his insights had staying power, his ex nilho deductive approach to physics is obviously at odds with the facts of reality. Is Descartes’ method any different in terms of essentials from those of modern physicists who seek to discover a “Theory of Everything,” a set of equations simple enough to write on a T-shirt from which reality may be rigorously deduced [[xiv]]? The contemporary approach is on a much more abstract level, substituting poly-dimensional geometric structures for nebulous notions about the perfection of God. To be sure, contemporary physicists require that their theories match the experimental data. Even more important to some contemporary theorists, however, are concerns for “beauty” and “symmetry.”

In any event, Descartes’ life-long habits of leisurely contemplation may well have been his undoing. Queen Christina of Sweden (1626–1689) hired the philosopher and physicist to be her personal tutor. Arriving in Stockholm in the middle of the winter, he discovered the Queen expected him to be available every morning at 5 am. The stress and the cold were too much for Descartes, and he succumbed to pneumonia within weeks.

In the next episode, our attention shifts across the channel where we will learn that the discovery of gravitation took more than merely a fortuitous apple impacting an occiput.

Follow Online:

You may follow me online in other places as well:

Telegram: 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕔𝕫𝕒𝕣'𝕤 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕥𝕣𝕖𝕒𝕞

Gab: @aetherczar

Twitter: @aetherczar

Amazon: Hans G. Schantz

References

[i] René Descartes, Discourse on Method, Part V 43-44, D.A. Cress, trans. (Indianapolis, IN: Hacket Publishing Co., 1987), p. 23. Originally published in 1637.

[ii] Randall, Op. Cit. p. 32.

[iii] René Descartes, Discourse on Method, Part IV 32-33, Op. Cit., p. 17. This dictum may be said to constitute putting Descartes before the horse.

[iv] Shiffman, Mark, “Humanity 4.5,” First Things, November 2015. See: https://www.firstthings.com/article/2015/11/humanity-45

[v] Descartes, Op. Cit., Part VI, Op. Cit., p. 49.

[vi] A. Rupert Hall, From Galileo to Newton, Dover, New York, 1981, p. 115. Originally published in 1963.

[vii] Ibid. p. 117.

[viii] Ibid. p. 118.

[ix] I lack the space in the margin to reproduce Fermat's proof.

[x] Whittaker, Edmund, History of the Theories of Æther and Electricity, vol. 1, New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1951, p. 127.

[xi] https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1918610

[xii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User%3APortolanero

[xiii] Ibid. pp. 114-115.

[xiv] Lederman, Leon and Dick Teresi, The God Particle: If the Universe is the Answer, What is the Question?, p. 21.

[xv] Nils Forsberg After Pierre Louis Dumesnil (1698-1781), René Descartes i samtal med Sveriges drottning, Kristina. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ren%C3%A9_Descartes_i_samtal_med_Sveriges_drottning,_Kristina.jpg

Descartes has always been celebrated for his contributions to mathematics rather than physics. Mathematics is internally self-consistant, so it's something that you can do while lounging in your bed. I turned away from theoretical physics because too much of it involves the creation of incomprehensible mathematical constructs which are supposed to explain the universe. Most of these can never be tested, only inferred through observation, much as Descartes did. Mathematics is the language of physics, but just because you are a virtual "poet" in that language doesn't mean that what you say is true or makes sense.

Stigler's Law:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_examples_of_Stigler%27s_law