4.2.1 Ancient Views

From "Souls," "Atmospheres," and "Effluvia," to a Fluid Theory

If your email has truncated this post, click on the title to be transported to the online version.

Electric and magnetic observations date from antiquity. A Chinese Emperor in 2638 BC was said to use a compass to navigate his chariot through fog [[i]]. An embedded magnet was said to rotate a jade figurine to always point south, as in Figure 4.9. Other sources say this was a more recent invention of the ninth century, AD [[ii]].

Thales of Miletus (624/623–~548/545 BC) was the first to observe static electricity from amber [[iii]]. He also commented on magnetic attraction. According to Aristotle, “Thales, too, to judge from what is recorded about him, seems to have held soul to be a motive force, since he said that the magnet has a soul in it because it moves the iron” [[iv]].

Compasses appeared in Europe by the thirteenth century. The Florentine philosopher and statesman Brunetto Latini (1210–1294) mentioned their utility to mariners, but added, “No master mariner dares use it, lest he fall under the supposition of being a magician” [[v]].

In 1269, the French scholar, Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt (1240–1299), wrote the first known treatise on magnetism, detailing his experiments [[vi]]. Noting that a spheroidal magnet or lodestone tended to orient needles so as to girdle the stone the same way in which lines of longitude encompass the Earth, Peregrinus dubbed the magnet’s ends its “poles” [[vii]]. Figure 4.9 also shows his floating compass. One historian discounts the notion of a Chinese origin for the compass altogether, arguing that the compass was a medieval European invention [[viii]].

During his epic 1492 voyage, Christopher Columbus (~1451–1506) was astonished to compare his compass to the north star and discover that his compass, normally aligned just slightly east of true north in coastal and Mediterranean waters, deviated westward to align with true north, and then ended up 11 degrees west of true north at the westernmost part of his journey [[xiii]]. This remarkable discovery of the agonic line–the line on which a compass needle aligns with true north–took on added significance for two reasons.

First, it is said to have influenced Pope Alexander VI in his Papal Bull of 1493, dividing the Atlantic into Spanish and Portuguese spheres of influence. Second, it was thought that Columbus’ agonic line might replace the Meridian of Ferro (El Hierro), the line of longitude running through what was once thought to be the westernmost point of the known (old) world [[xiv]]. The agonic line would have made a poor long-term geographic reference, however. Figure 4.10 superimposes a nineteenth century analysis of the location of the agonic line with the voyages of Columbus and John Cabot (~1450–~1500) [[xv], [xvi]] who first discovered it [[xvii]]. By 2000, continuing motion of the magnetic pole shifted the agonic line comfortably west into the Gulf of Mexico.

Mariners heavily relied upon compasses by the sixteenth century. Miscreants who dared misdirect a ship by interfering with a compass faced savage punishments, including having their hand pinned to the mast with a dagger or a “keel hauling,” as in the 1555 engraving of Figure 4.11 [[xix]]. Magnetic phenomena remained surrounded by mystery and were the source of many legends and folk tales. Well into the seventeenth century mariners still feared great magnetic mountains of lodestone, reputed to be able to hold their ships in place or even pull the nails out of their hulls [[xx]].

We have the English physicist, William Gilbert (1544–1603), court physician to Queen Elizabeth and her successor King James I, to thank for one of the earliest comprehensive treatises on electricity and magnetism. The magnetic insights of Petrus Peregrinus lay gathering dust in a handful of university libraries. Only 28 copies of the 1269 manuscript are known to have existed, and a portion of the text only appeared in print in 1558. Four years later in 1562, a Belgian scholar, Johannes Taisnerius (1508–1562) copied verbatim portions of Peregrinus’ work on a magnetic perpetual motion machine, and he passed it off as his own [[xxi]]. Denouncing the plagiarizer, Gilbert exclaimed:

Such an engine Petrus Peregrinus, centuries ago, either devised or delineated after he had got the idea from others; and Joannes Taysner published this, illustrating it with wretched figures, and copying word for word the theory of it. May the gods damn all such sham, pilfered, distorted works, which do but muddle the minds of students! [[xxv]]

Gilbert uncovered a copy of the work of Petrus Peregrinus in his thorough investigations of the state of magnetic knowledge.

Gilbert also built upon the work of the English compass maker Robert Norman, who in his 1576 text noticed that his compass needles not only oriented themselves in a horizontal plan to indicate north, but also in a vertical plane [[xxvi], [xxvii]].

In de Magnete, Gilbert extended upon the analogy Peregrinus identified between magnets and the globe. Gilbert concluded that in fact the Earth was a giant magnet or lodestone, and correctly identified the relation in the dip in elevation with the magnetic latitude. Figure 4.12 shows Norman’s dip-circle, Gilbert, and Gilbert’s diagram of magnetic dip. Gilbert further adopted Norman’s idea that magnetic effects occur within a certain sphere of influence around the magnet–the “orbis viriutis” or orb of virtue [[xxviii]]. Gilbert explained how to assess the strength of a magnet:

All lodestones are tested for strength in the same way, viz., with a versorium (rotating needle) held at some distance ; the stone that at the greatest distance is able to make the needle go round is the best and strongest [[xxix]].

In Gilbert’s interpretation, a magnet has a fixed sphere of influence within which it can act. He hypothesized that the Earth itself could act as far as the moon and that magnetic force played a role in the motions of the planets.

Gilbert also considered the mysterious force exerted by amber (“ήλεκτρο” or “ilektro,” in Greek), and dubbed the materials that generate this force, “electrics” [[xxx]]. Thus, did electricity get its name [[xxxi]]. Rather than merely a phenomenon unique to amber and a few other materials, Gilbert identified a wide variety of substances including glass, sulfur, sealing wax and others that exhibit electric behavior [[xxxii]]. Because their effects were unleashed through friction, Gilbert hypothesized some “atmosphere of effluvia” around electrified bodies was responsible, an idea alluded to by Isaac Newton, also [[xxxiii]].

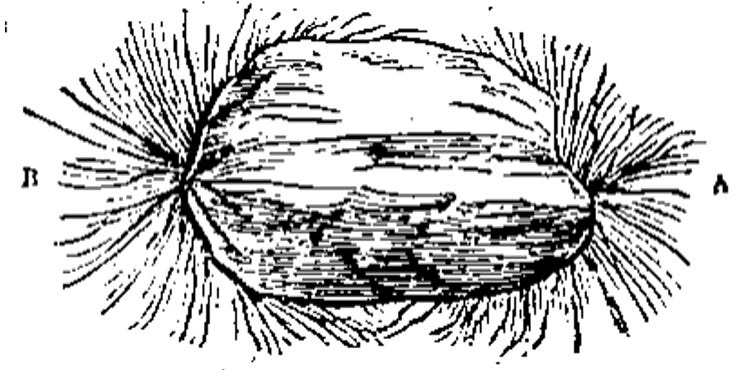

Italian Jesuit philosopher and scientist, Niccolò Cabeo (1586–1650), noted attraction and repulsion were both characteristics of electric effects [[xxxiv]]. He is also credited with employing iron filings to trace out magnetic field patterns, as in Figure 4.13 [[xxxv]]. This 1629 diagram is the first known depiction of magnetic field lines.

The German scientist, inventor, and politician, Otto von Guericke (1602–1686) – who we have already encountered for his pioneering work with vacuum pumps – implemented a large sulfur ball that could be spun and charged via friction to create substantial electrostatic effects on which he reported. The friction was thought to mechanically drive off a subtle electric atmosphere responsible for electric influences. Figure 4.14 shows von Guericke, his sulfur globes, and his electric machine.

Vague appeals like these to “souls” responsible for life-like electric and magnetic motions and “effluvia” emitted from electric and magnetic objects and responsible for their effects within a certain orb of virtue remained credible hypotheses for how electricity and magnetism work.

English gentleman scientist, Stephen Gray (1666–1736), left his career dyeing cloth to work as an astronomer, building telescopes. The failure of the Cambridge Observatory where he was employed, and his own poor health and inability to resume dyeing work, left Gray in poverty. A pension and accommodation in The Charterhouse, a retirement home for impoverished gentlemen, gave him the freedom to pursue his investigations. Before Gray’s studies, electric effects appeared tied to the bodies on which they were created through friction. Possibly caught in the middle of one of Newton’s feuds, only after Newton’s death did the Royal Society begin publishing Gray’s results [[xxxix]]. The result of Gray’s pioneering work was the discovery of electric current, and the first fluid theories of electricity.

Next time: 4.2.2 Fluid Theories of Electricity

Follow Online:

You may follow me online in other places as well:

Telegram: 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕔𝕫𝕒𝕣'𝕤 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕥𝕣𝕖𝕒𝕞

Gab: @aetherczar

Twitter: @aetherczar

Amazon: Hans G. Schantz

References

[i] Mottelay, Paul Fleury, Bibliographical History of Electricity and Magnetism, London: Charles Griffin & Company Limited, 1922, p. 1

[ii] Benjamin, Park, A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise in Electricity) From Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin, New York: John Wiley & Sons: 1898, p. 389.

[iii] Mottelay, Op.Cit., p. 7.

[iv] Aristotle, On the Soul, Book 2. See The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revise Oxford Translation, Jonathan Barnes, ed. Princeton University Press, 1985, pp. 645-646.

[v] Mottelay, Op.Cit., p. 48.

[vi] Mottelay, Op.Cit., pp. 45-54.

[vii] Whittaker, Edmund, History of the Theories of Æther and Electricity, vol. 1, New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1951, pp. 33-34.

[viii] Benjamin, Park, A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise in Electricity) From Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin, New York: John Wiley & Sons: 1898, Chapter III.

[ix] Benjamin, Park, A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise in Electricity) From Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin, New York: John Wiley & Sons: 1898, p. 73.

[x] Illustration from "Illustrerad verldshistoria utgifven av E. Wallis. volume I": Thales. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thales_of_Miletus#/media/File:Illustrerad_Verldshistoria_band_I_Ill_107.jpg

[xi] Bertelli, Timoteo, Sulla epistola di Pietro Peregrino di Maricourt e sopra alcuni trovati e teorie magnetiche del secolo XIII, Rome: Tipografia Delle Scienze Matematiche E Fiche, 1868, Figure 10, end plate. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Sulla_epistola_di_Pietro_Peregrino_di_Ma/NZxpIHQt1TEC?hl=en&gbpv=1

[xii] Modified from “Map of the Voyages of Columbus and Cabot,” Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) See: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nzsqcmsp

[xiii] Mottelay, Paul Fleury, Bibliographical History of Electricity and Magnetism, London: Charles Griffin & Company Limited, 1922, pp. 65-67.

[xiv] Brother Potamian and James J. Walsh, Makers of Electricity, New York: Fordham University, 1909, pp. 23-25.

[xv] Mottelay, Paul Fleury, Bibliographical History of Electricity and Magnetism, London: Charles Griffin & Company Limited, 1922, p. 69.

[xvi] I went looking for accounts of John Cabot’s voyage to try to back up Brother Potamian’s account, only to discover that no one is really sure whether Cabot survived his second voyage and returned or not, such was the state of record keeping. All the more credit goes to Columbus when we realize the extent of his accurate record keeping. Any plots of Cabot’s supposed course on historical maps are wild guesses. I also couldn’t find any other sources to back up the story about the Papal Bull and the proposal to move the Meridian of Ferro. It may be apocryphal. It may be another overlooked nugget of poorly documented history. If you happen to uncover more on this interesting question, do please let me know.

[xvii] Report of the Superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Showing the Progress of the Work during the Fiscal Year Ending With June, 1886, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1887, pp. 404-405.

[xviii] Benjamin, Park, A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise in Electricity) From Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin, New York: John Wiley & Sons: 1898, p. 145. Figure originally from Olaus Magnus’ History of the Northern Nations, ed. of 1555.

[xix] Benjamin, Park, A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise in Electricity) From Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin, New York: John Wiley & Sons: 1898, p. 145. Figure originally from Olaus Magnus’ History of the Northern Nations, ed. of 1555.

[xx] Benjamin, Park, A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise in Electricity) From Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin, New York: John Wiley & Sons: 1898, pp. 19, 96-102.

[xxi] Brother Potamian and James J. Walsh, Makers of Electricity, New York: Fordham University, 1909, pp. 26-28.

[xxii] Norman, Robert, The Newe Attractive, Shewing the Nature Propertie, and Manifold Virtues of the Lodestone ; with the Declination of the Needle, Touched therewith, Under the Plain of the Horizon, London, reprinted 1720, p. 17. Originally printed 1576.

[xxiii] William Gilbert (1544–1603), Oil on wood, 35.5 x 27.5 cm See: https://infogalactic.com/w/images/3/3e/William_Gilbert_45626i.jpg

[xxiv] Gilbert, William, de Magnete, P. Fleury Mottelay, translator, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1893, p. 122. Originally published in Latin in 1600.

[xxv] Gilbert, William, de Magnete, P. Fleury Mottelay, translator, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1893, p. 166. Originally published in Latin in 1600.

[xxvi] Norman, Robert, The Newe Attractive, Shewing the Nature Propertie, and Manifold Virtues of the Lodestone ; with the Declination of the Needle, Touched therewith, Under the Plain of the Horizon, London, reprinted 1720, p. 17.

[xxvii] Brother Potamian and James J. Walsh, Makers of Electricity, New York: Fordham University, 1909, p. 29.

[xxviii] Gilbert, William, de Magnete, P. Fleury Mottelay, translator, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1893, p. 122. Originally published in Latin in 1600.

[xxix] Gilbert, William, de Magnete, P. Fleury Mottelay, translator, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1893, p. 167. Originally published in Latin in 1600.

[xxx] Gilbert, William, de Magnete, P. Fleury Mottelay, translator, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1893, p. 75. Originally published in Latin in 1600.

[xxxi] Sir Thomas Browne introduced the general term for the phenomenon, “electricity,” in 1646. See Whittaker, p. 35.

[xxxii] Whittaker, p. 35.

[xxxiii] Whittaker, pp. 36-37. See Querry 22 of Newton’s Opticks.

[xxxiv] Whittaker, Edmund, History of the Theories of Æther and Electricity, vol. 1, New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1951, pp. 33-36.

[xxxv] Brother Potamian and James J. Walsh, Makers of Electricity, New York: Fordham University, 1909, p. 3.

[xxxvi] Cabeo, Nicolao, Philosophia Magnetica, in qua Magnetis Natvra Penitvs Explicatvr, 1629, p. 18.

[xxxvii] Otto von Guericke. Line engraving.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). See: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/wu33rtj8/items?langCode=eng&canvas=1

[xxxviii] Benjamin, Park, A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise in Electricity) From Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin, New York: John Wiley & Sons: 1898, p. 389.

[xxxix] Peck, M., “Review of Newton’s Tyranny: The Suppressed Scientific Discoveries of Stephen Gray and John Flamsteed,” Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 27(4), 2004, pp. 734–735. doi:10.2514/1.11197.

you made me learn things💖😖💖

When it comes to the advances of our ancient ancestors, I suspect there are a LOT of Hidden Truths