Einstein became a global celebrity following the formal joint session of the Royal Philosophical Society and the Royal Astronomical Society in London where Dyson and Eddington announced their eclipse results on November 6, 1919 [[i]], “the day on which Einstein was canonized,” in the words of his biographer, Abraham Pais (1918–2000) [[ii]].

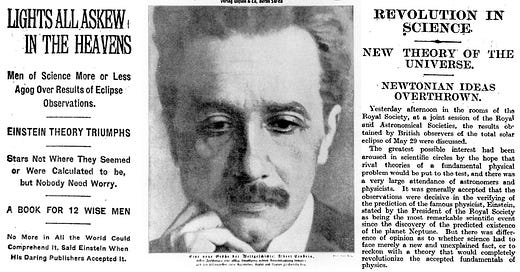

“LIGHTS ALL ASKEW IN THE HEAVENS,” proclaimed The New York Times on November 10, 1919. “When he offered his last important work to the publishers,” the paper reported breathlessly, “he warned them there were not more than twelve persons in the whole world who would understand it, but the publishers took the risk” [[iii]].

“A new greatest in world history: Albert Einstein, whose research meant a complete re-evaluation of our view of nature and is equivalent to the discoveries of Copernicus, Kepler and Newton,” declared the December 14, 1919 cover of the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung under a full-page cover picture of a thoughtful and brooding Einstein [[iv]]. As one scholar points out:

The BIZ [Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung] stood at the forefront of a new trend in journalism in which photography rather than the printed word dominated the page. Few remembered the stories, but the BIZ’s images left a lasting impression on many of its million-plus subscribers, nearly three times that of the popular Berliner Tageblatt. Editor-in-chief Kurt Korff exploited the camera’s potential for conveying the dramatic events of the day, and its impact on popular culture in Germany was enormous. On top of this, Einstein was unusually photogenic, which helps to account for why people were constantly taking snapshots of him. His son-in-law, Rudolf Kayser, found the famous title-page portrait for BIZ at once authentic and powerful, noting how it evoked a sense of awe in and reverence for the man heralded as the greatest scientific genius of the day [[v]].

Even the normally staid and conservative Times (of London), then as now the paper of record for the British Empire, got in the act with headlines asserting a “REVOLUTION IN SCIENCE” and “NEWTONIAN IDEAS OVERTHROWN.”

In part, this may have been a case where the “Jewish Press sanctifies a fellow Jew” [[ix]]. In 1896, a Jewish newspaperman from Chattanooga, Tennessee, Adolph Ochs (1858–1935), bought and eventually secured control over The New York Times. Soon thereafter, Ochs adopted the slogan “All the News That’s Fit to Print” on the masthead. He favored comprehensive and trustworthy news gathering over the “yellow” (sensationalist) journalism characteristic of the period [[x]]. By and large, Ochs worked to avoid The New York Times being perceived as a Jewish paper [[xi]].

When a Jewish pencil-factory manager in Atlanta, Georgia, Leo Frank (1884–1915), was accused of the murder of his fourteen-year-old employee, Mary Phagan (1899–1913), during Passover in 1913, Ochs’ paper largely ignored the case [[xii]]. In the Jim-Crow South, an all-White jury (including several Jews) believed the testimony of Black janitor Jim Conley (1886–1962?) and indicted Frank. Another jury convicted the prominent White man of the heinous crime.

As Frank appealed his conviction, a Jewish businessman (and pioneer of modern advertising), Albert David Lasker (1880–1952), appealed to Ochs. The newspaperman took up Frank’s cause with such fervor that he “so infuriated Georgians that Frank’s death at the hands of a lynch mob became almost inevitable” [[xvi]].

Ochs’ strident advocacy both alienated White Southerners (offended at being characterized as ignorant antisemites and racists), and angered Black Southerners (appalled at the racist invective hurled at Jim Conley, the Black witness and accessory on whom Frank’s team tried to pin the entire responsibility for the crime) [[xvii]]. Ochs and The New York Times were not above throwing their weight around in the service of Jewish causes.

Berliner Illustrite Zeitung was similarly a Jewish-owned weekly magazine, until “Aryanized” in the early years of the Nazi regime [[xviii]].

Weeks before the formal announcement, the popular paper Berliner Tageblatt, known in antisemitic circles as the “Judenblatt,” or the Jew Paper, published an extravagant description of the eclipse results. The Polish-Jewish author of the article, Alexander Moszkowski (1851–1934), a friend of Einstein, declared “a highest truth, beyond Galileo and Newton, beyond Kant” had been unveiled by “an oracular saying from the depth of the skies” [[xix], [xx]].

Einstein published his own note on the eclipse results in the German-language equivalent of the English-language flagship science journal, Nature: Die Naturwissenschaften, whose founder and editor-in-chief, Arnold Berliner (1862-1942), was also Jewish [[xxi], [xxii]]. Berliner printed pieces on relativity, both pro and con, but wasn’t above putting his thumb on the scale for Einstein. A talented German experimental optical physicist, Ernst Gehrcke (1878–1960), published his objections to relativity in 1913, in Die Naturwissenschaften, calling relativity “an interesting case of mass suggestion in physics, especially in the lands [where German is spoken]” [[xxiii]]. Max Born answered Gehrcke soon thereafter [[xxiv]]. Berliner accepted another Gehrcke paper for publication and sent printer’s proofs to Einstein as a courtesy. When Einstein objected, Berliner pulled Gehrcke’s article at the last minute, an imposition that understandably annoyed Gehrcke [[xxv]].

Berliner’s ultimate fate was grossly out of proportion to any slight he may have inflicted, however. On August 13, 1935, the Nazis “Aryanized” Dr. Arnold Berliner, removing him from the editorship of Die Naturwissenschaften, the journal he’d founded in 1913 [[xxvi]]. He visited the US in 1935 and 1937, but declined opportunities to stay there [[xxvii]]. Berliner died by suicide in Berlin on March 22, 1942, the day before he would have been deported to a camp by the Gestapo [[xxviii]].

There is more to the story of Einstein’s popularity, however, than the simplistic narrative of Jews backing one of their own. The Times (of London) can hardly be charged with being a Jewish paper, for instance. Editor-in-chief, Henry Wickham Steed (1871–1956), was accused of antisemitism [[xxix]] after publicizing The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in The Times in May 1920 [[xxx]], only a few months after their laudatory coverage of Einstein. Steed subsequently published an exposé of The Protocols as fraudulent the following year in May 1921 [[xxxi]].

While Einstein was enthusiastically promoted by his co-religionists at The New York Times, Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, Berliner Tageblatt, and Die Naturwissenschaften, a wider range of influencers and narrative architects rallied to express similar sentiments.

The story, after all, was rather compelling. At the November 6, 1919 announcement of the eclipse results, President of the Royal Society J. J. Thomson (1856–1940) called the findings a “momentous pronouncement of human thought,” and added that “the Einstein theory must now be reckoned with, and that our conceptions of the fabric of the universe must be fundamentally altered.” What was the other side of the debate? Long-time champion of classical physics, continuity, and the æther theory, Oliver Lodge (1851–1940) rose… and left the meeting without a word [[xxxiv], [xxxv]].

Then, in a letter to the editor the next day, Lodge excused his absence because of a previous engagement and offered a couple of alternative classical hypotheses that could explain the eclipse result [[xxxvi]]. “Two weeks later, Newton’s defender [Lodge] dramatically capitulated in the pages of The Times in dramatic fashion, and in such a way as to emphasize the mathematical incomprehensibility of Einstein’s theory” [[xxxvii]].

If Einstein’s predictions were verified, Lodge predicted (as was quoted in The Times) that “Einstein’s theory would dominate all higher physics and the next generation of mathematical physicists would have a terrible time.” If the theory and its implications were true, it would be left “to the younger men” to deal with them, and that “he himself would not be competent to do so,” being content to “leave the transcendental methods to others” [[xxxviii]].

The New York Times also ran the story. “So complicated has this revolutionary theory proved that even some of the most learned have been confounded” [[xxxix]].

Lodge and others continued to offer tentative alternative explanations, but the narrative rapidly crystalized and the sensational message was clear – Einstein’s theory had triumphed, and it was so complex not even specialists could understand it. What hope could an average person have? The Times editorialized a few days later, admitting that they “can’t understand Einstein,” a confession amplified by The New York Times the next day.

However difficult it may have been to understand them, Einstein’s accomplishments delighted many Germans, eager to take credit for them as a point of pride following the crippling loss in World War I. Similarly many English shied away from regarding Einstein as “German,” one of their hated enemies. When The Times (of London) solicited an article from Einstein, not long after the eclipse results triumph, he quipped some prophetic words:

By an application of the theory of relativity to the taste of readers, today in Germany I am called a German man of science, and in England I am represented as a Swiss Jew. If I come to be regarded as a bête noire, the descriptions will be reversed, and I shall become a Swiss Jew for the Germans and a German man of science for the English! [[xlii]]

Other Germans, however, objected to the growing cult of Einstein [[xliii]] for technical or personal reasons, and their disagreements spiraled out of control in a vast positive feedback loop [[xliv], [xlv]]. Even in scientific circles, opinions were mixed.

Many scientists admired the aesthetic beauty of Einstein’s approach despite holding some scientific reservations. In 1955, some fifty years after Einstein debuted his theory of special relativity, his good friend, Max Born (1882–1970), confided:

The foundation of general relativity appeared to me then, and still does as the greatest feat of human thinking about Nature, the most amazing combination of philosophical penetration, physical intuition, and mathematical skill. But its connection with experience is slender. It appealed to me like a great work of art, to be admired and enjoyed at a distance [[xlvi]].

Director of the Manhattan Project, J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967), an American physicist born to German-Jewish immigrants, opined:

…Einstein’s work was widely understood and widely applied, but there are always those who didn’t like it as there are always those who didn’t like the painting of Cézanne or the quartets of Beethoven [[xlvii]].

New Zealand nuclear physicist Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937) similarly declared:

The theory of relativity, quite apart from its validity, cannot but be regarded as a magnificent work of art [[l]].

Relativity in general and General Relativity in particular were as much works of art as of science. The theories inspired objections from those who did not share Einstein’s aesthetics.

Einstein faced opposition to his ideas as soon as he published them. For instance, Philipp Lenard (1862–1947) initiated a cordial correspondence with Einstein not long after the former received the 1905 Nobel Prize for his discovery of the photoelectric effect and the latter published his quantum explanation of it [[li]]. Lenard took issue with Einstein’s interpretation and the two agreed to disagree. Lenard further found himself in disagreement with relativity and wrote a critical paper, “Über Relativitätsprinzip, Äther, Gravitation” [“On the Relativity Principle, Æther, Gravitation”] in 1918 [[lii], [liii]].

In 1916, Gehrcke uncovered and popularized Paul Gerber’s calculation of Mercury’s perihelion advance, arguing that Einstein plagiarized Gerber, or at least that the problem had already been solved [[liv]]. German astronomer Hugo von Seeliger (1849–1924) countered that Gerber made a crude math error [[lv]].

“Einstein replied to these and other objections in the form of a dialogue between a ‘critic’ and a ‘relativist,’ written in a relaxed tone, with just a touch of condescension” [[lvi]]. As Galileo (1564–1642) found out when he wrote Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in 1632 and placed the objections of Pope Urban VIII (1568–1644) in the mouth of a simpleton character named “Simplicio,” this was not an effective way for Einstein to endear himself to his critics [[lvii], [lviii]].

In February 1920, protestors disrupted Einstein’s lectures at the University of Berlin [[lix]], but not to make a political statement. Einstein had opened his lectures to the public, and his tuition-paying students protested the resulting disruptions and lack of seats [[lx]]. In March 1920, Prussian civil servant Wolfgang Kapp (1858–1922) and Prussian General Walther Karl Friedrich Ernst Emil Freiherr von Lüttwitz (1859–1942) shattered the peace in Berlin [[lxi]]. The Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch aimed to replace the Weimar Republic with a military dictatorship and chased the Weimar government out of Berlin, but collapsed in four days after a general strike was called [[lxii]]. Times were tense.

That summer, Paul Weyland (1888–1972), a German political activist and engineer (with questionable credentials), organized the “Working Group for German Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science,” a mysteriously well-funded group which aimed to “educate” the German public about relativity [[lxiii], [lxiv]]. One researcher characterized Weyland’s group as:

…a phantom that existed only in his advertisements and on the stationery that he used for his letters. No other member of that association has ever been known, and although Weyland called it a registered association (“eingetragener Verein”), there is no trace of this association in any register in Berlin. Although even a Berlin newspaper wrote in 1920 that nothing was known about the members of that association, it is up to this day mentioned in secondary literature as an institution that had really existed and combated relativity [[lxv]].

Weyland’s one-man crusade kicked off on August 6, 1920 with an article echoing Gehrcke’s themes, calling relativity “scientific mass hypnosis,” “a big hoax,” and that it was plagiarized [[lxvi], [lxvii]].

Weyland reached out to many German physicists critical of Einstein. He offered substantial fees to participate in his lecture program [[lxix]]. Gehrcke agreed to attend and address the inaugural public meeting [[lxx]].

Weyland rented the Berlin Philharmonic Hall and delivered his presentation on August 24, 1920, reiterating the points from his previous article [[lxxi]].

Weyland maintained that Einstein had resorted to propagandistic methods when academic criticism had risen too high--and at the same time he had obstructed and suppressed academic critics. All of this was a consequence of the intellectual and moral decay of German society, which was being exploited and promoted by “a certain press.” This decay had “attracted all kinds of adventurers, not only in politics, but also in art and science.” Indeed, the theory of relativity was being “thrown to the masses” in exactly the same way as “the dadaist [abstract art] gentlemen” promoted their wares, which had to do as little as relativity with the observation of nature. No one should be surprised, therefore, Weyland concluded, that a movement had arisen to counter this “scientific Dadaism” [[lxxii]].

Gehrcke echoed similar talking points, but in a calm and factual way at sharp contrast with Weyland’s demagoguery [[lxxiii], [lxxiv]].

Attending in the company of his friend, 1920 Nobel Laureate for Chemistry, Walther Hermann Nernst (1864–1941), Einstein cackled loudly at times and at the end pronounced the entire event ‘most amusing’” [[lxxv]]. Einstein was not truly as amused as he claimed, however, because within days he was threatening to leave Berlin, making no secret of his discontent [[lxxvi]].

“Gehrcke and Weyland had not been explicitly anti-Semitic, nor did they overtly criticize Jews in their speeches” [[lxxvii]]. Weyland’s allusions to “a certain press,” however, were references to the Jewish papers that had so heavily promoted Einstein. And rabble-rousers in the audience had made crass anti-Semitic remarks within his earshot [[lxxviii]].

Einstein concluded his opposition was politically motivated – not an unreasonable conclusion given the anti-Semitic literature and swastika lapel pins his friend, 1914 Nobel Laureate for Physics Max von Laue (1879–1960), noted being sold at the venue [[lxxix]]. Einstein also assumed Lenard was involved, since Lenard’s academic critique of relativity was available at the meeting, and Weyland listed Lenard as a scheduled future speaker.

However, Lenard had declined to participate in Weyland’s meeting, preferring to make his case in a more official forum, a meeting of the German Society of Scientists and Physicians scheduled at the resort of Bad Nauheim the following month. “The letters from Lenard and to Lenard that have been preserved from this time already suggest that he was wrongly associated with Weyland’s actions” [[lxxx]].

Einstein’s friends promptly defended him in the press. Einstein’s own response, “My Reply—About the Antirelativistic Association,” appeared on the front page of Berliner Tageblatt on August 27, 1920. Einstein’s biographer, Albrecht Fölsing (1940–2018) describes it as “a searing polemic, angry and vicious.”

I am fully aware of the fact that both speakers are unworthy of a reply from my pen; for, I have good reason to believe that there are other motives behind this undertaking than the search for truth. (Were I a German national, whether bearing a swastika or not, rather than a Jew of liberal international bent...) I only respond because I have received repeated requests from well-meaning quarters to have my view made known [[lxxxi]].

Einstein began with an appeal to authority…

First of all I observe that to my knowledge hardly any scientists today who have made any substantial contribution to theoretical physics do not concede that the entire theory of relativity is logically and consistently structured and that it agrees with the verified experimental data now available [[lxxxii]].

… and insulted Lenard [[lxxxiii], [lxxxiv]]:

From among physicists of international renown I can only name Lenard as an outspoken critic of relativity theory. I admire Lenard as a master of experimental physics; however, he has yet to accomplish something in theoretical physics, and his objections to the general theory of relativity are so superficial that I had not deemed it necessary until now to reply to them in detail [[lxxxv]].

Einstein further accused both Lenard and Gehrcke of making a personal attack.

The personal attack Messrs. Gehrcke and Lenard have launched against me based on these circumstances [by their promotion of Gerber’s earlier perihelion advance result] has been generally regarded as unfair by real specialists in the field; I had considered it beneath my dignity to waste a word on it [[lxxxvi]].

“This was unfair to Gehrcke, who had limited his criticism to purely scientific matters and had punctiliously refrained from any personal comments about Einstein” [[lxxxvii]]. In addition to not having been present at the meeting, Lenard similarly had “invariably maintained an academic tone” throughout his discussions of relativity [[lxxxviii]].

Two days later, in an interview, Einstein summed up his opinion of the situation in Berlin vividly: “I feel like a man lying in a good bed, but plagued by bedbugs” [[lxxxix]].

Such incivility prompted criticism, even from Einstein’s friends. Fölsing reports Ehrenfest was unable to believe that “at least some of the phrases were written by your own hand” [[xc]]. “My wife and I absolutely cannot believe that you yourself wrote some of the phrases in the article,” Ehrenfest added. “If you really did write them down with your own hand, it proves that these damn pigs have finally succeeded in touching your soul. I urge you as strongly as I can not to throw one more word on this subject to that voracious beast, the public” [[xci]].

Max Born’s wife, Hedwig Born (1891–1972), was worried about the possible consequences of the “maladroit reply” in the Tageblatt: “Anyone not knowing you might get a wrong picture of you. That, too, is painful” [[xcii]].

Prominent German theoretical physicist and chairman of the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft (German Physical Society), Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld (1868–1951), who had followed “the Berlin campaign against you with real fury,” summed up various people’s opinion of the article to the effect that it was regarded as “not very happy and not really like yourself” [[xciii]].

Sommerfeld did apparently have misgivings about Einstein’s relationship with the Jewish press, suggesting he address his critics in the Süddeutsche Monatshefte, a conservative paper with reactionary tendencies. “The Berliner Tageblatt,” Sommerfeld added, “does not appear to me the right place to settle accounts with the brawling anti-Semites” [[xcvi]]. Sommerfeld made no criticism, though, of Einstein’s worst remark: “But the thing about the bedbugs was good” [[xcvii]].

“Lenard, as a professor at Heidelberg and a Nobel Laureate, felt deeply insulted, and he demanded that Einstein apologize in a public manner. But this Einstein refused to do” [[xcviii]]. Both men headed to Bad Nauheim for the annual meeting of the “Gesellschaft Deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte” (the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians).

The official record of the Bad Nauheim conference describes “useless but civilized debate” [[xcix]] and “unproductive” [[c]] discussion [[ci]]. One report, however, claims the meeting threatened to be a riot and police kept protestors outside the meeting hall [[cii]].

The chairman of the session on relativity, Max Planck (1858–1947), kept a tight rein on the proceedings and the audience inside the hall [[civ]], although Max Born recalled at one point, “Einstein was provoked into making a caustic reply” [[cv]]. A few weeks later, Einstein wrote Born to assure him that he would “not allow myself to get excited again as in Nauheim” [[cvi]].

Prevailed upon by friends, Einstein allowed them to publish a statement in a Berlin newspaper expressing “his strong regrets for having directed reproaches against Herr Lenard, whom he values highly,” but Lenard never forgave the insult [[cvii]]. After the Bad Nauheim meeting, Weyland’s anti-relativity campaign fell apart. Gehrcke concluded that Weyland was a “dubious type.” Lenard agreed: “Unfortunately, Weyland turned out to be a crook” [[cviii]].

Modern sensibilities may hinder understanding the unprecedented nature of the publicity campaign surrounding Einstein and his work. When Max Born wrote a book on relativity in 1920, he included a frontispiece portrait of Einstein and a biography of Einstein’s life [[cix]]. Shocked, Max von Laue insisted “that he and many other colleagues would take umbrage at the photograph and the biography. This sort of thing does not belong in a scientific book, even if it is intended for a broader readership” [[cx]]. Born interceded with the publisher to delete the photograph and the biography from future printings [[cxi]].

That incident may help modern readers understand the reaction of Einstein’s friends to the discovery that he had collaborated on a biography with his friend, Alexander Moszkowski. A self-confessed proponent and booster of the “cult of Einstein” [[cxiii]], Moszkowski had written the fawning piece about Einstein in Berliner Tagblatt in 1919. His previous books included collections of jokes and books on the occult. Einstein’s friends were horrified.

"This book will constitute your moral death sentence for all but four or five of your friends,” insisted Hedwig Born. “It could subsequently be the best confirmation of the accusation of self-advertisement” [[cxiv]]. Max Born agreed. “You’ve got to shake off this M[oszkowski], otherwise Weyland will have won along the whole line, and Lenard and Gehrcke will triumph” [[cxv]].

Einstein sent Moszkowski “a registered letter to the effect that his splendid opus must not be printed” [[cxvi]]. “It might be doubted that Einstein was serious about this prohibition of the publication. He deliberately refrained from enforcing the prohibition by legal means, and he remained on good terms with Moszkowski, continuing to treat him as a friend” [[cxvii]].

Moszkowski’s book, Einstein, Insights into his Worldview; Common-sense observations about the theory of relativity and a new world system, developed from conversations with Einstein, appeared in 1921.

An English translation came out a few years later under the less grandiose title, Einstein: The Searcher. The preface set the tone:

THE book which is herewith presented to the public has few contemporaries of a like nature ; it deserves special attention inasmuch as it is illuminated by the name Albert Einstein, and deals with a personality whose achievements mark a turning-point in the development of science…

One might endeavour, then, to decide to whom mankind owes the greater debt, to Euclid or to Archimedes, to Plato or to Aristotle, to Descartes or to Pascal, to Lagrange or to Gauss, to Kepler or to Copernicus… If we then further selected only those who saw far beyond their own age into the illimitable future of knowledge, this great number of celebrities would be considerably diminished. We should glance away from the milestones, and fix our gaze on the larger signs that denote the lines of demarcation of the sciences, and among them we should find the name of Albert Einstein…

… the range of Einstein’s genius extends much further than is generally surmised by those who have busied themselves only with the actual physical theory. It sends out rays in all directions, and brings into view wonderful cosmic features under his stimulus — features which are, of course, embedded in the very refractory mathematical shell of his physics which embraces the whole world. But only minds of the distant future, perhaps, will be in a position to realize that all our mental knowledge is illuminated by the light of his doctrine [[cxviii]].

Elsewhere, Moszkowski said “...we proclaim Einstein as the Galilei of the twentieth century...” [[cxix]].

“In his personal utterances Einstein is always so charming—quite unlike the foolish publicity circus that has been set in motion for him,” declared the German mathematician, Felix Klein (1849–1925) [[cxx]]. That publicity circus was a mere sideshow compared to all three rings awaiting Einstein when “the Galilei of the twentieth century” would travel to America, a land where science had come to public relations, and public relations had come to science.

Next time: 5.2.8: Einstein Comes to America: Science Comes to Public Relations and Public Relations to Science.

Enjoyed the article, but maybe not quite enough to spring for a paid subscription?

Then click on the button below to buy me a coffee. Thanks!

Full Table of Contents [click here]

Follow Online:

You may follow me online in other places as well:

Telegram: 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕔𝕫𝕒𝕣'𝕤 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕥𝕣𝕖𝕒𝕞

Gab: @aetherczar

Twitter: @aetherczar

Amazon: Hans G. Schantz

References

[[i]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 238.

[[ii]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 305.

[[iii]] The New York Times, November 10, 1919. See: https://www.nytimes.com/1919/11/10/archives/lights-all-askew-in-the-heavens-men-of-science-more-or-less-agog.html

[[iv]] Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung cover December 14, 1919. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albert_Einstein_by_Suse_Byk.png

[[v]] Rowe, David E., “Einstein’s Allies and Enemies: Debating Relativity in Germany, 1916-1920,” V.F. Hendricks, K.F. Jørgensen, J. Lützen and S.A. Pedersen (eds.), Interactions: Mathematics, Physics and Philosophy, 1860-1930, Springer, 2006, pp. 231–280. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5195-1_8

[[vi]] The New York Times, November 10, 1919. See: https://www.nytimes.com/1919/11/10/archives/lights-all-askew-in-the-heavens-men-of-science-more-or-less-agog.html

[[vii]] Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung cover December 14, 1919. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albert_Einstein_by_Suse_Byk.png

[[viii]] Excerpts from The Times, published 7-8 November 1919 (Royal Society Press Cuttings PC/1/28). See: https://royalsociety.org/blog/2024/08/observing-relativity/

[[ix]] Bjerknes, Christopher Jon, The Manufacture and Sale of Saint Einstein, 2006. More recent edition in five volumes on Amazon. See: https://amzn.to/3PnzNul

[[x]] The Editors, Encyclopaedia Britannica entry: “Adolph Simon Ochs.” See: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Adolph-Simon-Ochs#ref754367

[[xi]] Cruikshank, Jeffrey L., and Arthur W. Schultz, The Man Who Sold America: The Amazing (But True!) Story of Albert D. Lasker and the Creation of the Advertising Century, Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2006, p. 130. See: https://amzn.to/4fIpM5H

[[xii]] Cruikshank, Jeffrey L., and Arthur W. Schultz, The Man Who Sold America: The Amazing (But True!) Story of Albert D. Lasker and the Creation of the Advertising Century, Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2006, p. 128. See: https://amzn.to/4fIpM5H

[[xiii]] Photo of Leo Max Frank (1884–1915). Bain News Service - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ggbain.13934. This work is from the George Grantham Bain collection at the Library of Congress. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Frank#/media/File:Leo_Frank.jpg

[[xiv]] A 1913 Photo of Mary Phagan (1899–1913), Atlanta Georgian (newspaper) - Crop from copy Of Atlanta Journal kept at archive.org/stream/AtlantaGeorgianNewspaperAprilToAugust1913/atlanta-georgian-042813#. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Frank#/media/File:Mary_Phagan.jpg

[[xv]] Adolph Ochs (1858–1935); cropped from a TIME Magazine Cover Featuring Adolph S. Ochs (1 Sep 1924). See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolph_Ochs#/media/File:TIMEMagazine1Sep1924.jpg

[[xvi]] Cruikshank, Jeffrey L., and Arthur W. Schultz, The Man Who Sold America: The Amazing (But True!) Story of Albert D. Lasker and the Creation of the Advertising Century, Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2006, pp. 6, 128-129. See: https://amzn.to/4fIpM5H

“Sometimes Lasker failed, and failed spectacularly. In the notorious Leo Frank case (1913-1914), he and his media allies (including not only Arthur Brisbane but also Adolph Ochs of the New York Times) so infuriated Georgians that Frank’s death at the hands of a lynch mob became almost inevitable” (p. 6).

“The first significant coverage of the Frank case in the Times, four columns’ worth, ran on February 18, 1914, when the Supreme Court of Georgia denied Frank a new trial.!° Frank’s story now became an obsession for the Times, which produced more than a hundred articles—about the case, the prisoner, and his fight to stay alive—over the next year and a half. When the Times weighed in, other publications took note, so Times owner Adolph Ochs was largely responsible for stirring up a national media frenzy about an obscure local case that had already been decided and its verdict upheld.

“And it was Albert Lasker who persuaded Ochs to take up the seemingly lost cause of Leo Frank” (pp. 128-129).

[[xvii]] Historical Research Department of the Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews 3 The Leo Frank Case: The Lynching of a Guilty Man, Chicago: Nation of Islam, 2016, pp. 224-232. See: https://store.finalcall.com/product/the-secret-relationship-between-blacks-and-jews-volume-3/.

[[xviii]] Peter de Mendelssohn, Zeitungsstadt Berlin: Menschen und Mächte in der Geschichte der deutschen Presse, Berlin: Ullstein, 1959, p. 393.

[[xix]] van Dongen, Jeroen, “Reactionaries and Einstein's Fame: ‘German Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science,’ Relativity, and the Bad Nauheim Meeting,” November 9, 2011. See: https://arxiv.org/abs/1111.2194.

[[xx]] Moszkowski, Alexander “Die Sonne bracht’es an den Tag,” Berliner Tageblatt (October 8, 1920, Evening Edition). See Christopher Jon Bjerknes, The Manufacture and Sale of Saint Einstein, 2006, pp. 18-20. More recent edition in five volumes on Amazon. See: https://amzn.to/3PnzNul

[[xxi]] van Dongen, Jeroen, “Reactionaries and Einstein's Fame: ‘German Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science,’ Relativity, and the Bad Nauheim Meeting,” November 9, 2011. See: https://arxiv.org/abs/1111.2194.

[[xxii]] Rowe, David E., “Einstein’s Allies and Enemies: Debating Relativity in Germany, 1916-1920,” V.F. Hendricks, K.F. Jørgensen, J. Lützen and S.A. Pedersen (eds.), Interactions: Mathematics, Physics and Philosophy, 1860-1930, Springer, 2006, pp. 231–280. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5195-1_8.

[[xxiii]] Gehrcke, E. “Die gegen die Relativitatstheorie erhobenen Eimvande,” Die Naturwissenschaften, Vol. 1, 1913, pp. 62-66. Cited by Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 461.

[[xxiv]] Born, Max, “Zum Relativitatsprinzip: Entgegnungen auf Herm Gehrckes Artikel,” Die Naturwissenschaften, Vol. 1, 1913, pp. 92-94. Cited by Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 461.

[[xxv]] Rowe, David E., “Einstein’s Allies and Enemies: Debating Relativity in Germany, 1916-1920,” V.F. Hendricks, K.F. Jørgensen, J. Lützen and S.A. Pedersen (eds.), Interactions: Mathematics, Physics and Philosophy, 1860-1930, Springer, 2006, pp. 231–280. See p. 244. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5195-1_8.

[[xxvi]] Anon., “Dr. Arnold Berliner and Die Naturwissenschaften,” Nature, vol. 136, 28 September 1935, p. 506. (1935). https://doi.org/10.1038/136506a0. See: https://rdcu.be/d6NiO

[[xxvii]] Thatje, Sven, “Dr Arnold Berliner (1862-1942), physicist and founding editor of Naturwissenschaften,” Die Naturwissenschaften, vol. 100, no. 12, pp. 1105-1107. Doi: 10.1007/s00114-013-1124-4. See: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259201901_Dr_Arnold_Berliner_1862-1942_physicist_and_founding_editor_of_Naturwissenschaften

[[xxviii]] Anon., “Dr. Arnold Berliner,” Nature, vol. 150, 5 September 1942, p. 284.

[[xxix]] Liebich, Andre, “The antisemitism of Henry Wickham Steed. Patterns of Prejudice,” Patterns of Prejudice, vol. 46, no. 2, April 19, 2012, pp. 180–208. See: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0031322X.2012.672226

“On 8 May 1920 The Times (London) devoted an entire column to The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, which had recently been translated into English under the title The Jewish Peril. This was not the first review of the pamphlet but what some took to be the imprimatur of The Times gave it unprecedented importance.”

[[xxx]] Steed, Henry Wickham, “A Disturbing Pamphlet: A Call for Enquiry,” The Times, May 8, 1920.

[[xxxi]] Steed, Henry Wickham, “An exposure, the source of the Protocols: truth at last,” The Times, 16 August 1921. Three articles exposing the forgery by Philip Perceval Graves were printed in The Times on 16, 17 and 18 August 1921, and immediately reprinted as the pamphlet, Philip Perceval Graves, The Truth about ‘The Protocols’: A Literary Forgery (London: The Times 1921). As cited by Liebich, Op. Cit.

[[xxxii]] Clipped from the New York Times, November 25, 1919. See: https://www.nytimes.com/1919/11/25/archives/a-new-physics-based-on-einstein-sir-oliver-lodge-says-it-will.html?searchResultPosition=1

[[xxxiii]] Oliver Lodge at his home using a punch-ball. Anonymous - Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. 12 April, 1930. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Lodge#/media/File:Oliver_Lodge_1930.png

[[xxxiv]] Anon., “REVOLUTION IN SCIENCE; NEW THEORY OF THE UNIVERSE; NEWTONIAN IDEAS OVERTHROWN,” The Times, Friday November 7, 1919, p. 12. “At this stage Sir Oliver Lodge, whose contribution to the discussion had been eagerly expected, left the meeting.” The Times Digital Archive, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CS203492711/TTDA?u=tou&sid=bookmark-TTDA. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

[[xxxv]] Crelinsten, Jeffrey, “Physicists receive relativity: Revolution and reaction,” The Physics Teacher, vol. 18, March 1980, pp. 115-122.

[[xxxvi]] Crelinsten, Jeffrey, “Einstein, relativity, and the press,” The Physics Teacher, vol. 18, March 1980, pp. 187-193.”

[[xxxvii]] Crelinsten, Jeffrey, “Einstein, relativity, and the press,” The Physics Teacher, vol. 18, March 1980, pp. 187-193.

[[xxxviii]] Crelinsten, Jeffrey, “Einstein, relativity, and the press,” The Physics Teacher, vol. 18, March 1980, pp. 187-193

[[xxxix]] Anon., “A NEW PHYSICS, BASED ON EINSTEIN; Sir Oliver, Lodge Says It Will Prevail, and Mathematicians Will Have a Terrible Time. SPACE OF FOUR DIMENSIONS In Which Gravity Ceases to be a Force and Becomes a Quality. ATTEMPT TO MEASURE IT Its Radios Put at 16,000,000 LightYears, or 80 Times the Distance to More Details Made Known,” The New York Times, November 25, 1919. See: https://www.nytimes.com/1919/11/25/archives/a-new-physics-based-on-einstein-sir-oliver-lodge-says-it-will.html?searchResultPosition=1

[[xl]] Clipped from The New York Times, November 29, 1919. See: https://www.nytimes.com/1919/11/29/archives/cant-understand-einstein.html?searchResultPosition=1

[[xli]] Clipped from The New York Times, November 29, 1919. See: https://www.nytimes.com/1919/11/29/archives/cant-understand-einstein.html?searchResultPosition=1

[[xlii]] Crelinsten, Jeffrey, “Einstein, relativity, and the press,” Physics Teacher, vol. 18, 1980, pp. 115-122. Note, The Times, replied to Einstein’s quip: “…we concede him his little jest. But we note that in accordance with the general tenor of his theory, Dr. Einstein does not supply any absolute description of himself.”

[[xliii]] Bjerknes, Christopher Jon, The Manufacture and Sale of Saint Einstein, 2006, p. 14. Citing A. Moszkowski to A. Einstein, translated by A. M. Hentschel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 8, Document 292, Princeton University Press, (1998), p. 281.

“Regardless of what happens, I would like to continue the ‘cult’; for you it is secondary, for me it is of paramount importance in life. Additionally, I have the encouraging feeling that, with my modest writing abilities, I may also serve the cause once in a while.” Jewish journalist Alexander Moszkowski wrote to Albert Einstein on 1 February 1917.

More recent edition in five volumes on Amazon. See: https://amzn.to/3PnzNul

[[xliv]] Crelinsten, Jeffrey, Einstein’s Jury: The Race to Test Relativity, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 164.

[[xlv]] van Dongen, Jeroen, “Reactionaries and Einstein's Fame: ‘German Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science,’ Relativity, and the Bad Nauheim Meeting,” November 9, 2011. See: https://arxiv.org/abs/1111.2194

[[xlvi]] Chandrasekhar, S., “Einstein and General Relativity: Historical Perspectives,” American Journal of Physics, vol. 47, no. 3, March 1979, pp. 212-217. See p. 213.

[[xlvii]] Crelinsten, Jeffrey, “Einstein, relativity, and the press,” Physics Teacher, vol. 18, 1980, pp. 115-122.

[[xlviii]] Philipp Lenard, (1900). Fair Use Claimed. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Phillipp_Lenard_in_1900.jpg

[[xlix]] Portrait of Gehrcke, E. (Ernst), 1878-1960. Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, W.F. Meggers Collection. Catalog ID: Gehrcke Ernst A1. Copyright, American Institute of Physics; used by permission. Collection info: fedora/nbla:287968. See: https://repository.aip.org/islandora/object/nbla%3A302485

[[l]] Chandrasekhar, S., “Einstein and General Relativity: Historical Perspectives,” American Journal of Physics, vol. 47, no. 3, March 1979, pp. 212-217. See p. 213.

[[li]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 138-139.

[[lii]] Lenard, Philipp, “Über Relativitätsprinzip, Äther, Gravitation,” 1920 (Originally published 1918). See: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/ssd?id=wu.89054462015

[[liii]] Lenard’s essay was updated and extended multiple times over the years. For a summary of the various editions, see: https://www-kritik--relativitaetstheorie-de.translate.goog/2011/08/uber-ather-und-urather/?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp

[[liv]] Gehrcke, E. “Zur Kritik und Geschichte der neueren Gravitationstheorien,” Annalen der Physik, Vol. 51, 1916, pp. 119-124. Cited by Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 461.

[[lv]] Seeliger, H. von, “Bemerkung zu dem Aufsatz des Herm Gehrcke “Uber den Ather” Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 20, 1918, p. 262. Cited by Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 461.

[[lvi]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 461.

[[lvii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 274.

[[lviii]] Rowe, David E., “Einstein’s Allies and Enemies: Debating Relativity in Germany, 1916-1920,” V.F. Hendricks, K.F. Jørgensen, J. Lützen and S.A. Pedersen (eds.), Interactions: Mathematics, Physics and Philosophy, 1860-1930, Springer, 2006, pp. 231–280. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5195-1_8.

“Only two interlocutors enter this mini-debate: a persistent, but open-minded Kritikus who queries Relativist, clearly a thinly-disguised pseudonym for the author. The tone Einstein struck at the outset was at once playful and sarcastic. Whether intended or not, it was also undoubtedly offensive to the two principals at which it was aimed, Ernst Gehrcke and Philipp Lenard, neither of whom shared Einstein’s penchant for irony.”

[[lix]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 526.

[[lx]] van Dongen, J., “Mistaken Identity and Mirror Images: Albert and Carl Einstein, Leiden and Berlin, Relativity and Revolution,” Phys. Perspect. Vol. 14, 2012, pp. 126–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00016-012-0084-y. See: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00016-012-0084-y

[[lxi]] van Dongen, Jeroen, “Reactionaries and Einstein's Fame: ‘German Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science,’ Relativity, and the Bad Nauheim Meeting,” November 9, 2011. See: https://arxiv.org/abs/1111.2194.

[[lxii]] Overbye, Dennis, Einstein in Love: A Scientific Romance, New York: Viking, 2000, p. 370.

[[lxiii]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 133.

[[lxiv]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein: A Biography, Ewald Osers, translator, New York: Viking, 1997, pp. 459-463

[[lxv]] Kleinert, Andreas, “Paul Weyland, the Einstein-Killer from Berlin,” Undated, see: https://websrv.physik.uni-halle.de/Fachgruppen/history/weyland.htm.

[[lxvi]] Weyland, Paul, “Einstein’s Relativitätstheorie--eine wissenschaftliche Massensuggestion,” Tägliche Rundschau, August 6, 1920, Evening Edition. As cited by van Dongen, Op. Cit.

[[lxvii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 461.

[[lxviii]] See: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alte_Philharmonie_Berlin#/media/Datei:Gedenktafel_Bernburger_Str_21_(Kreuzb)_Alte_Philharmonie.jpg [ ].

[[lxix]] Rowe, David E., “Einstein’s Allies and Enemies: Debating Relativity in Germany, 1916-1920,” V.F. Hendricks, K.F. Jørgensen, J. Lützen and S.A. Pedersen (eds.), Interactions: Mathematics, Physics and Philosophy, 1860-1930, Springer, 2006, pp. 231–280. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5195-1_8.

“Only two interlocutors enter this mini-debate: a persistent, but open-minded Kritikus who queries Relativist, clearly a thinly-disguised pseudonym for the author. The tone Einstein struck at the outset was at once playful and sarcastic. Whether intended or not, it was also undoubtedly offensive to the two principals at which it was aimed, Ernst Gehrcke and Philipp Lenard, neither of whom shared Einstein’s penchant for irony.”

[[lxx]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 461.

[[lxxi]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 274-275.

[[lxxii]] van Dongen, Jeroen, “Reactionaries and Einstein's Fame: ‘German Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science,’ Relativity, and the Bad Nauheim Meeting,” November 9, 2011. See: https://arxiv.org/abs/1111.2194.

[[lxxiii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein: A Biography, Ewald Osers, translator, New York: Viking, 1997, pp. 462

[[lxxiv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 288.

[[lxxv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 288.

[[lxxvi]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein: A Biography, Ewald Osers, translator, New York: Viking, 1997, p. 464.

[[lxxvii]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 290.

[[lxxviii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 275.

[[lxxix]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 462.

[[lxxx]] Schönbeck, Charlotte, Albert Einstein und Philipp Lenard: Antipoden im Spannungsfeld von Physik und Zeitgeschichte, Bayreuth, Germany: Springer, 2012, p. 26.

[[lxxxi]] Einstein, Albert, “My Reply. On the Anti-Relativity Theoretical Co., Ltd. [August 27, 1920]. Source: Albert Einstein, ‘Meine Antwort. Ueber die anti-relativitatstheoretische G. m. b. H.’ in Berliner Tageblatt, Ser. 49, No. 402, Morning Edition A, August 27, 1920, p. 1. Collected in Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources, Klaus Hentschel, Editor, Ann M. Hentschel, Editorial Assistant and Translator, Berlin: Birkhauser Verlag, 1996, pp. 1-5.

[[lxxxii]] Einstein, 1920, Op. Cit.

[[lxxxiii]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 316. Pais justifies this escalation, saying, “One may sympathize. By then, Lenard was already on his way to becoming the most despicable of all German scientists of any stature. Nevertheless, Einstein's article is a distinctly weak piece of writing, out of style with anything else he ever allowed to be printed under his name.”

[[lxxxiv]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 275.

[[lxxxv]] Einstein, 1920, Op. Cit.

[[lxxxvi]] Einstein, 1920, Op. Cit.

[[lxxxvii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 274.

[[lxxxviii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 466.

[[lxxxix]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463.

[[xc]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463.

[[xci]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 290.”

[[xcii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463.

[[xciii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463-464.

[[xciv]] Hedi Born Outdoors. Credit Line: Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Maria Stein Collection. Catalog ID: Born Max G12. Collection info:fedora/nbla:287919. Photo taken in India just after they left Germany. Hedi Born, dress, sitting, outdoors. See: https://repository.aip.org/islandora/object/nbla%3A292008

[[xcv]] Portrait of Arnold Sommerfeld. Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Sommerfeld Arnold A6. Collection info: fedora/nbla:287931. See: https://repository.aip.org/islandora/object/nbla%3A309045

[[xcvi]] Rowe, David E., “Einstein’s Allies and Enemies: Debating Relativity in Germany, 1916-1920,” V.F. Hendricks, K.F. Jørgensen, J. Lützen and S.A. Pedersen (eds.), Interactions: Mathematics, Physics and Philosophy, 1860-1930, Springer, 2006, pp. 231–280. See p. 244. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5195-1_8.

[[xcvii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463-464.

[[xcviii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 275.

[[xcix]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 316.

[[c]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463-464.

[[ci]] Einstein, Albert, Philipp Lenard, Hermann Weyl and Ernst Gehrcke, The Bad Nauheim Debate, 1920. A translation of reports on the conference is available here: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:The_Bad_Nauheim_Debate.

[[cii]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 135.

[[ciii]] Portrait of Max Born. Credit: 'Voltiana,' Como, Italy - September 10, 1927 issue, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Catalog ID: Born Max A13. Collection info:fedora/nbla:287873. See: https://repository.aip.org/islandora/object/nbla%3A292463

[[civ]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463-464.

[[cv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 292.

[[cvi]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 292.

[[cvii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 276.

[[cviii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 463-464.

[[cix]] Born, Max, Die Relativitätstheorie Einsteins, Berlin: Verlag von Julius Springer, 1920. “With 129 Text Illustrations and a Portrait of Einstein.” See: https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=1PhYAAAAYAAJ&rdid=book-1PhYAAAAYAAJ&rdot=1

[[cx]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 468-469.

[[cxi]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 262-263

[[cxii]] Photo of Alexander Moszkowski. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alexander_Moszkowski.jpg

[[cxiii]] Bjerknes, Christopher Jon, The Manufacture and Sale of Saint Einstein, 2006, p. 14. Citing A. Moszkowski to A. Einstein, translated by A. M. Hentschel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 8, Document 292, Princeton University Press, (1998), p. 281.

“Regardless of what happens, I would like to continue the ‘cult’; for you it is secondary, for me it is of paramount importance in life. Additionally, I have the encouraging feeling that, with my modest writing abilities, I may also serve the cause once in a while.” Jewish journalist Alexander Moszkowski wrote to Albert Einstein on 1 February 1917.

More recent edition in five volumes on Amazon. See: https://amzn.to/3PnzNul

[[cxiv]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 263

[[cxv]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 469-470.

[[cxvi]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 469-470.

[[cxvii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 263

[[cxviii]] Moszkowski, Alexander, Einstein, the searcher: his work explained from dialogues with Einstein, Henry L. Brose, Translator, London: Methuen & Co, Ltd, 1921, p. 142. See: https://archive.org/details/einsteinsearch00moszrich/page/142/mode/2up?q=galileo

[[cxix]] Moszkowski, Alexander, Einstein, the searcher: his work explained from dialogues with Einstein, Henry L. Brose, Translator, London: Methuen & Co, Ltd, 1921, p. 142. See: https://archive.org/details/einsteinsearch00moszrich/page/142/mode/2up?q=galileo

[[cxx]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 468.

“When he offered his last important work to the publishers,” the paper reported breathlessly, “he warned them there were not more than twelve persons in the whole world who would understand it, but the publishers took the risk”

Wasn't it Eddington who picked up on that canard? He said something like "...there are only three people in the world who understand relativity- Einstein, myself, and I can't think of who the third person is."

Hans, thanks for giving us a look at some of the precursor to Pop Culture fetishist propaganda that came to infect and poison Science. You are helping us to discover it's a short walk from researcher to popularizer to cult figure, even if not in the mind of the individual under the lime light, then at least for the audience who sees him.

Truth's light may be harsh, but at least it's less likely to lead one off a cliff.

Bernays' efforts can be mitigated with understanding of McLuhan's observations. We should be reading vigorously to understand both men these days.