5.2.9 What Is Meant By "Jewish Physics?"

And What Other Kinds of Physics Influenced Relativity & Quantum Mechanics?

Ideas some today might consider racist or antisemitic were pervasive among Weimar-era Germans. One very prominent German physicist declared:

… Jews are a group of people unto themselves. Their Jewishness is visible in their physical appearance, and one notices their Jewish heritage in their intellectual works, and one can sense that there are among them deep connections in their disposition and numerous possibilities of communicating that are based on the same way of thinking and of feeling [[i]].

The author of this provocative statement? Einstein, himself. Was Einstein right? Is there a distinctive style of thinking unique to Jews that is reflected in their intellectual and scientific works? We might follow Einstein’s thinking and start with the hypothesis that Jewish physics is merely physics created by a Jew. Even for relativity, this is difficult to justify.

On the one hand, the special theory of relativity is the result of trying to account for the experiment of two Americans (Michelson and Morley) in the work of a Dutchman (Lorentz), which when combined with the methodological insights of a German (Mach) and a Frenchman (Poincaré) led to conversations in Switzerland with his friends in the Olympia Academy from Romania (Maurice Solovine) and Italy (Michele Besso). On the other hand, Einstein does not put his theory’s multicultural heritage on display. In fact, it is remarkable that in his paper he cites none of his influences at all with the exceptions of thanking Besso for “several valuable suggestions” [[ii]].

Michelson [[iii]], and Besso [[iv]] were Jewish, as was Einstein who led the way. We could argue that while the story of relativity was told in many tongues, Einstein gave it a Jewish voice.

Was Quantum Mechanics “Jewish Physics?”

By this reasoning, relativity is Jewish physics because Einstein, who was the leading figure in the modern interpretation of relativity theory, was Jewish. Niels Bohr (1885–1962) was the father of the Copenhagen Interpretation and his mother was Jewish [[v]]. So, can we conclude that quantum physics is similarly “Jewish physics?”

That hypothesis becomes more difficult to maintain as we consider other quantum pioneers who broke the mold. Einstein’s friend, Max Born (1882–1970), acknowledged Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) as “the founder of the new theory” [[vii]]. Heisenberg was a member of the right-wing “White Knights,” a youth organization that was rolled into the Hitler Youth, and he was a member of the Freikorps who participated in the paramilitary operation to overthrow the Bavarian Soviet Republic. Moreover, he was sufficiently trusted by the Nazis that they appointed him head of their atomic weapons development program [[viii]]. Finally, Heisenberg was nominally a member of the Evangelische Kirche, a Lutheran/Calvinist faith [[ix]]. However, Heisenberg confided (rather ambiguously) to a friend, “If someone were to say that I had not been a Christian, he would be wrong. But if someone were to say that I had been a Christian, he would be saying too much” [[x]].

Einstein’s friend Max Born (1882–1970) and Pascual Jordan (1902–1980) collaborated to complete Heisenberg’s matrix formulation of quantum mechanics [[xi], [xii]], “the quintessential sort of ‘Jewish’ science — purely formalistic, completely removed from observation, entirely concerned with the ways in which one should manipulate the symbols” [[xiii]]. In 1928 Einstein proposed that Heisenberg, Born, and Jordan should share a Nobel Prize for their pioneering contributions to quantum mechanics [[xiv]].

Moreover, Jordan worked out a novel statistical description of the behavior of subatomic particles. He submitted his paper to Born, then the editor of Zeitschrift für Physik, in 1925. Born didn’t have time to read it and went on a lecture tour to America, forgetting about the paper in his suitcase [[xvii]]. Born explained:

“…when I came back home to Germany half a year later and unpacked, I found the paper at the bottom of the suitcase. It contained what came to be known as the Fermi-Dirac statistics. In the meantime, it had been discovered by Enrico Fermi and, independently, by Paul Dirac. But Jordan was the first” [[xviii]].

While Born was Jewish [[xix]], Jordan was “a member of the Nazi Party; and even became a storm trooper” [[xx]].

As early as 1930, three years before Adolf Hitler took power, Jordan was expressing extreme antidemocratic viewpoints in far-right journals under the pseudonym Ernst Domeier. Despite collaborating with many Jewish colleagues, Jordan joined the party in May 1933. He then proceeded to shed his pseudonym and began authoring a series of articles that were laden with Nazi ideology. Aimed at party leaders, the texts argued that supporting modern physics would be the key to winning future wars [[xxi]].

Jordan’s student, Engelbert Levin Schücking (1926–2015), commented in a biographical note:

Pascual Jordan was one of the great theoretical physicists of the century. But his attempt to modify general relativity with a variable gravitational constant did nothing to enhance his reputation. Nor did his conspicuous membership in the Nazi Party [[xxiv], [xxv]].

What of his other contemporaries who contributed to the development of quantum mechanics?

In addition to his contribution to Fermi-Dirac statistics, Englishman Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (1902–1984) developed a relativistic theory of quantum mechanics that describes electrons [[xxvi]]. Italian physicist Enrico Fermi (1901–1954) was a pioneer of nuclear physics [[xxvii]]. French physicist Louis de Broglie (1892–1987) pioneered the wave theory of quantum mechanics [[xxviii]] which was brought to fruition by Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961) [[xxix]]. None of these quantum pioneers were Jewish, although both Dirac and Fermi married Jewish women [[xxx]]. Fermi’s wife, Laura Capon Fermi (1907–1977), author of the delightful memoir Atoms in the Family, belonged to a family of nonobservant Jews [[xxxi]].

The evolving political situation and threat to his wife from antisemitic laws prompted Enrico Fermi to travel from his 1938 Nobel Prize win in Stockholm to America with his wife and children [[xxxii]]. Thus in 1942, Chicago hosted the world’s first nuclear reactor, not Rome [[xxxiii]].

Born’s first research assistant, Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli (1900–1958), identified the “Pauli Principle,” that “[t]wo electrons with identical quantum numbers cannot coexist in an atom” [[xxxiv]]. Pauli was raised Roman Catholic, but came from a Jewish family with roots in Prague [[xxxv]].

The great German physicist, Arnold Sommerfeld (1868–1951), taught the first university course on relativity in Germany [[xxxvi]]. He made pioneering contributions to the early development of quantum theory [[xxxvii]]. His doctoral students included four Nobel laureates, Hans Bethe (1906–2005), Peter Debye (1884–1966), Heisenberg, and Pauli [[xxxviii]]. Bethe’s mother was Jewish, although he was raised as Protestant [[xxxix]]. Debye was a Dutch Catholic who succeeded Einstein and von Laue as head of the Physics Institute of the Kaiser Wilhem Institute under Hitler’s Nazi regime before leaving behind his home and all his possessions, to flee Germany in 1940 [[xl]].

If quantum mechanics is to be called “Jewish science,” it cannot be because the pioneers and creators of quantum mechanics were all Jewish. Clearly, they were not. A mix of Jewish and non-Jewish scientists were responsible. This caused problems for physicists jockeying for bureaucratic favor under the Nazi regime. They invented the concept of a “White Jew,” to libel someone like Heisenberg who may not have been racially Jewish but nevertheless endorsed or advocated so-called Jewish science [[xli]].

Fortunately, Heisenberg had connections. His mother knew the mother of Heinrich Himmler (1900–1945), one of the most powerful figures in Nazi Germany, and the man who served as the head of the SS (Schutzstaffel) and later as Chief of the Gestapo and Minister of the Interior. At Mrs. Heisenberg’s request, Mrs. Himmler interceded with her son [[xlii]].

When Heisenberg appealed directly to Himmler, Himmler investigated personally and ordered the SS to leave Heisenberg alone. “I believe that Heisenberg is a decent person, and we cannot afford to lose or to kill this man, who is relatively young and can educate a new generation” [[xliv], [xlv], [xlvi]].

Do You Have To Be Jewish To Create Jewish Science?

If Jewish science isn’t necessarily science created by a Jew, is it nevertheless possible, in Einstein’s words, to notice Jewish heritage in intellectual works? Are there “deep connections in their disposition and numerous possibilities of communicating that are based on the same way of thinking and of feeling?”

Many of Einstein’s contemporaries agreed with his assessment. Sommerfeld wrote to Lorentz, complaining about Einstein’s derivations:

... As ingenious as they are, it seems to me that there is something almost unhealthy in their nonconstructive and nonvisualizable dogmatics. An Englishman would hardly have put forth such a theory; perhaps ... what is expressed here is the conceptually abstract nature of the Semite. I hope you will be able to breathe some life into this ingenious conceptual framework [[xlvii]].

Sommerfeld did not mean this in a derogatory fashion at all. “I have now studied Einstein, who impresses me greatly,” he wrote to Wilhelm Wien (1864–1928) in 1906 [[l]]. Sommerfeld was the first teacher to offer a course in relativity (1908–1909) and may have been the first to offer a course in Bohr’s quantum mechanics (1914–1915) [[li]]. For his principled defense of Einstein and modern physics, Sommerfeld, along with Heisenberg, was also pilloried as a ‘White Jew’ [[lii]].

Physicist and historian, Hans C. Ohanian (1941– ) argues:

Sommerfeld’s remarks are merely a frank, objective appraisal of Einstein’s theory, and that Jews are intellectually inventive and inclined to abstruse, convoluted arguments is a widely held view, even held by Jews themselves - it may be prejudicial, but it is not derogatory. Einstein himself described one of his Jewish colleagues in Zurich as a Rohbinerkopf, a rabbinical thinker [[liii]].

“I am confident that Jewish physics is not to be killed,” Einstein wrote to Born in 1944 [[liv]]. Born replied:

I have always appreciated your good Jewish physics, and have greatly enjoyed it; but I have done it myself on only one occasion, in the case of non-linear electrodynamics, and this was hardly a success. It is my honest opinion that when average people try to get hold of the laws of nature by thinking alone, the result is pure rubbish [[lv], [lvi]].

Max Born did not regard his work on the fundamentals of quantum theory, abstract and formalistic as it was, as “Jewish physics.” He narrowly defined Jewish physics as physics “by thinking alone,” by gedankenexperiment or thought experiment. The approach had worked for Einstein in devising special relativity. That definition may be too narrow to encompass the full range of Jewish influences on the development of science.

Einstein had what might be called a “loose” sense of the connection between theory and observation. For instance, when asked what his reaction would be if the eclipse observations and measurements disproved the bending of light predicted in general relativity, Einstein replied, “Then I would feel sorry for the good Lord. The theory is correct anyway” [[lvii]]. On the other hand, during a debate with Walther Nernst (1864–1941), Einstein offered a countervailing opinion.

…Nernst spoke of a certain causal relationship, whereupon Einstein remarked: “I do not think that this relationship holds good.” “But my esteemed colleague,’ replied Nernst, “it is just this relationship upon which you yourself quite recently insisted in a lecture.” To his amazement he received the following reply: “How can I help it if the Good Lord will not ratify what I maintained in my lecture?” [[lviii]]

There was also a sense in which Einstein treated his physics as word games and threw consistency out the window whenever it suited his immediate purposes. This is nowhere more evident than in Einstein’s treatment of what physicists would now call “observables.”

Einstein’s special relativity presented what might be called an “instrumentalist” or “operationalist” perspective. The speed of light appears constant to all observers. The laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames.

Einstein took what an observer would see and measure as primary and controlling in his theory. He did away with any speculation about underlying processes or mechanisms that might give rise to these observed phenomena. No æther required. And anyone who objected, as we have seen, he dismissed as either ignorant or antisemitic or both.

The shoe was on the other foot, however, when Einstein’s successors applied a radical version of his own perspective to quantum mechanics.

When Einstein first heard Heisenberg present his new theory of quantum mechanics in the famous Berlin colloquium series hosted by Planck, he was shaken. Afterward, the great man invited Heisenberg home to talk. Immediately, Einstein complained that in Heisenberg’s formulation the concept of the “electron path” had no place! Heisenberg, who had read Einstein’s work on relativity carefully, quoted Einstein back to him, pointing out that since we cannot, in fact, ever observe such a path, it made no sense to introduce the concept into the theory. (Einstein had made similar arguments when advancing parts of his relativity theory.) Much to Heisenberg’s amazement, Einstein replied, “Perhaps I did use such a philosophy earlier, and also wrote it, but it is nonsense all the same” [[lxi], [lxii]].

We have already seen how the positivist philosophy pioneered by Ernst Mach (1838–1916) and the relativity theory of Henri Poincaré (1854–1912) were influences on Einstein. What were Einstein’s other specific philosophic inspirations?

Einstein’s early education in Jewish teachings was limited. His family was irreligious, and he attended a Catholic school. His parents brought in an older relative to educate young Albert on his Jewish heritage [[lxv]]. This awakened in Einstein a sense of Jewish culture. There was one Jewish thinker, however, who did greatly influence Einstein’s scientific thinking.

Einstein and his university friends met regularly to discuss physics and philosophy starting in 1902, a group they dubbed the “Olympia Academy.” The most significant influence on young Einstein, was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese and Jewish extraction, Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) [[lxvi]].

From the reading list of the Olympia Academy, we know that Einstein had recently read Spinoza’s Ethics, and the axiomatic-deductive treatment in the first section of Einstein's paper on relativity is reminiscent of the first pages of Spinoza’s book, with its definitions, axioms, and deductions. Einstein revered Spinoza; after a visit to Spinoza’s house during a visit to Leiden in 1920, he wrote a long poem in his honor beginning with the line: “How much do I love that noble man, more than I could say with words ... ” [[lxvii]]

What Spinoza inspired in Einstein was a deep conviction of the causal connections of physical reality.

Although he lived three hundred years before our time, the spiritual situation with which Spinoza had to cope peculiarly resembles our own. The reason for this is that he was utterly convinced of the causal dependence of all phenomena, at a time when the success accompanying the efforts to achieve a knowledge of the causal relationship of natural phenomena was still quite modest [[lxviii]].

Einstein’s thinking was in tension between the contradictory premises of Mach and Spinoza. Mach objected to speculations about physical reality, saying only perceptions and observations matter. Spinoza insisted upon the essential unity of physical reality and its causal connectedness, even if the connections weren’t readily apparent. Early in his career, Einstein was a committed devotee of Mach and framed relativity in terms of observables, arguing that underlying mechanisms or processes were superfluous. Those who objected to his dismissal of mechanism or process, Einstein dismissed as ignorant or antisemitic, or both.

Ironically, Mach was not impressed with the relativity theory his teachings had inspired. “I do not consider the Newtonian principles as completed and perfect,” Mach acknowledged, “yet in my old age I can accept relativity just as little as I can accept the existence of atoms” [[lxix]].

As Einstein matured, however, Spinoza held a stronger grip on Einstein’s thinking. As we shall see, Einstein insisted upon causal connections between physical phenomena, arguing that “God does not play dice with the universe” [[lxx]]. Having led the charge toward positivism, instrumentalism, and operationalism, the older Einstein changed his mind, and sided increasingly with Spinoza and realism. “At that time [1905] my mode of thinking was much nearer positivism than it was later on,” Einstein recalled in a 1948 letter. “My departure from positivism came only when I worked out the general theory of relativity” [[lxxi]].

The elder Einstein held a deep and sincere belief in realism. “The very fact that the totality of our sense experiences is such that, by means of thinking, it can be put in order, this fact is one that leaves us in awe,” he wrote [[lxxii]].

“The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility. The fact that it is comprehensible is a miracle” [[lxxiii]]. He argued, “… a priori, one should expect a chaotic world which cannot be grasped by the mind in any way. There lies the weakness of positivists and professional atheists.” He continued elsewhere, “I have no better expression than ‘religious’ for this confidence in the rational nature of reality and in its being accessible, to some degree, to human reason. When this feeling is missing, science degenerates into mindless empiricism” [[lxxiv]].

Physicist and science historian Gerald Holton (1922 – ) noted that:

In the end, Einstein came to embrace the view which many, and perhaps he himself, thought earlier he had eliminated from physics in his basic 1905 paper on relativity theory: that there exists an external, objective, physical reality which we may hope to grasp— not directly, empirically, or logically, or with fullest certainty, but at least by an intuitive leap, one that is only guided by experience of the totality of sensible “ facts.” Events take place in a “real world,” of which the space-time world of sensory experience, and even the world of multidimensional continua, are useful conceptions, but no more than that [[lxxv]].

The very aspects of relativity and quantum theory that led critics to dismiss it as “Jewish physics,” the emphasis on observables and abstract thinking at the expense of a firm grounding in causal connections in physical reality, those were largely inspired by Mach. The Jewish influence of Spinoza on Einstein was likely what led to Einstein’s own critique of the “Jewish physics” aspects of quantum mechanics.

Are There Other Kinds of Physics?

So is there such a thing as Jewish physics after all? Even some who argue “…there is no ‘Jewish physics,’ there is only ‘physics,’” acknowledge that “one’s cultural milieu may well contribute to one’s approach to the way in which one approaches problem solving and, in general, answering questions…” [[lxxvi]]. If there is such a thing as Jewish science, however widely or narrowly we might define it, are there alternative schools or approaches to science against which we might compare and contrast the Jewish approach?

Sommerfeld noted an Englishman would never have put forth a theory with nonconstructive and nonvisualizable dogmatics. German physicist Paul Peter Ewald (1888–1985) observed that “…the English masters keep the two parts (theory and experiment) together” [[lxxvii]]. 1911 Nobel Laureate in Physics, Wilhelm Wien (1864–1928) told Ernst Rutherford “The relativity theory is something that you Anglo-Saxons will never understand, because it requires a genuine German feeling for abstract speculation” [[lxxviii]]. And we have already seen how French physicist and historian Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem (1861–1916) decried the English predilection to turn science from an abode of reason into a factory floor with the English insistence on mechanical models of the æther [[lxxix]].

This English approach to physics, grounded in Robert Grosseteste (~1169–1253), and Roger Bacon (~1219–1292), coming to fruition in Isaac Newton (1643–1727), bursting forth with Michael Faraday (1791–1867) and James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879), and culminating with Oliver Heaviside (1850–1925) and Heinrich Hertz (1857–1894) is one of the primary branches of physical science, at least from the electromagnetic perspective. It emphasizes the tie between theory and observation and the importance of concrete physical models through which to understand and interpret a mathematical description of reality. And with Hertz being one of the greatest exemplars of that approach, it’s clear that neither British ancestry nor an allegiance to the English crown is required to practice “English science.”

Other schools of science developed in contrast or in opposition to the English school. The French Rationalist school, for instance, pursued mathematical models and abstraction as a means of acquiring deeper understanding. We saw how Pierre Louis Maupertuis (1698–1759) generalized Newtonian dynamics through defining the principle of least action, how Guillaume François Antoine, Marquis de l’Hôpital (1661–1704), regarded Newton’s laws as “a priori deductions of pure thought,” and how Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) boldly declared he had no use for figures and diagrams, only exact algebraic expressions.

Duhem explained how the “ … French or German physicist conceives, in the space separating two conductors, abstract lines of force having no thickness or real existence…” [[lxxxi]]. The nationalistic French physicist Henri Bouasse (1866–1953) declared, “The French spirit with its desire for Latin lucidity will never understand the theory of relativity. It is a product of the Teutonic tendency to mystical speculation” [[lxxxii]]. As we will see, the French physicist, Louis de Broglie (1892–1987) had a profound influence on the development of quantum mechanics.

What of this supposed Teutonic tendency to mystical speculation? The other school of science with a profound influence on the development of quantum mechanics was distinctively German: the German Idealist or Natural Philosophy (Naturphilosophie) tradition. The German poet and scientist, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language, was a major influence on German thought. His scientific work spanned botany, to the theory of colors and beyond.

Goethe expressed his opinions on science in his play, Faust: A Tragedy. In the play, Dr. Heinrich Faust, a scholar, is dissatisfied with his book learning and seeks more knowledge, power, and the love of the beautiful but simple girl, Gretchen. He makes a deal with Mephistopheles (Satan), which takes Faust on a wild journey of indulgence and passion ending in heartbreak and disaster. At one point, Mephistopheles declares to Faust:

I counsel you, my dear young friend,

A course of Logic to attend.

Your mind will then be so well braced,

In Spanish boots so tightly laced,

That henceforth, by discretion taught,

’Twill creep along the path of thought,

And not, with all the winds that blow,

Go Will-o’-Wisping to and fro.

Logic, in Goethe’s view, tightly braces the mind like the infamous torturous boots the Inquisition used to extract confessions. Once tightly laced, the student’s mind must move slowly, cautiously, and methodically. While this prevents intellectual chaos, it also kills spontaneity, imagination, creativity, and inspiration.

Goethe cautioned that logic has shortcomings, and Germans listened. In his 1930 work, Physics and Philosophy, Heisenberg quoted this very passage at greater length, decrying the “narrowness of simple logical patterns” [[lxxxv]].

As we look further into quantum mechanics we will see that while many Jewish scientists were involved in developing the theory, it wasn’t uniquely “Jewish Science.” Instead quantum mechanics was deeply influenced by German Romanticism – as channeled through Goethe’s Mephistopheles – and Mach’s Austrian Logical Positivism.

These more abstract discussions of philosophic, cultural, social, and religious influences on the development of physics have their place in understanding the often-overlooked premises we take for granted behind the scientific concepts involved in relativity and quantum mechanics. However, it must never be forgotten that these ideas had severe and sometimes devastating real-world consequences.

Attacks on “Jewish Physics” By Proponents of “German Physics”

Einstein’s dismissal of critics as ignorant or antisemitic or both became a self-fulfilling prophecy. While there was probably little Einstein could have done personally to deflect the course of the broader cultural currents hurtling Germany to disaster, Einstein’s arrogant refusal to engage seriously with his serious critics pushed away scientists who were once allies and supporters.

We left the story of Einstein’s German opponents in September 1920. Einstein lashed out at his critic, Nobel Laureate Philipp Lenard (1862–1947), falsely accusing him of complicity with the anti-relativity meeting organized by Paul Weyland (1888–1972) in which physicist Ernst Gehrcke (1878–1960) participated. The more formal meeting of the German Society of Scientists and Physicians at the resort of Bad Nauheim the following month, hosted a showdown on the subject of relativity. Fearing an unseemly brawl, Planck arranged the program to emphasize mathematical and technical papers, limiting the time available for Lenard to dissent. Planck accomplished his mission at the expense of seriously engaging with Lenard’s arguments [[lxxxvi], [lxxxvii]].

Writing in 1969 about the 1920 Bad Nauheim events, Born claimed that “…Lenard directed some sharp, malicious attacks against Einstein, which were undisguisedly antisemitic” [[lxxxviii]]. As previously noted, this does not align with other contemporary accounts [[lxxxix], [xc]]. “This was evidently a projection backward from Lenard’s behavior after the Nauheim conference,” concluded Einstein biographer and physicist Albrecht Fölsing (1940–2018) [[xci]].

Nevertheless, there were vociferous and organized interruptions of Einstein’s remarks from the audience, tightly reined in by panel chairman, Max Planck (1858–1947) [[xcii]]. Einstein was provoked into an angry reply at one point which he later regretted [[xciii], [xciv]].

Privately, Einstein acknowledged he had overstepped in his exchanges before Bad Nauheim, writing to Born, “Everyone has to sacrifice at the altar of stupidity from time to time, to please the Deity and the human race. And this I have done thoroughly with my article” [[xcv], [xcvi]]. Einstein’s friends persuaded him to apologize, which he did, albeit in an indirect way. He allowed to be offered on his behalf “his strong regrets for having directed reproaches against Herr Lenard, whom he values highly” [[xcvii]]. Lenard refused to accept the apology offered on Einstein’s behalf by two colleagues [[xcviii]]. Sommerfeld wrote Einstein’s wife, Elsa, after Bad Nauheim that was pleased “the whole crisis was settled with more or less propriety. The principal merit, of course, belongs to your husband, to his kindness and factual manner—qualities one cannot credit his opponent Lenard with” [[xcix], [c]].

We pick up the story, here, with a bit more about Lenard and his prior relations with Einstein. In 1891, under the direction of his half-Jewish mentor, Heinrich Hertz (1857–1894), Lenard began his meticulous experimental work on cathode rays – beams of electrons. Upon Hertz’s death, Lenard set aside his own work to guide Hertz’s final book through publication [[ci]].

Though Lenard soon landed a professorship, it was at an institution without experimental resources. He resigned to take a post as a simple assistant at a different institution where he could continue his experimental work [[cii]]. Lenard’s difficulties and frustrations finding a congenial working environment had serious professional consequences.

While Lenard was struggling, Wilhelm Röntgen (1845–1923), a more senior researcher (who Lenard had advised and assisted) completed work that led to the discovery of X-rays and the award of the very first Nobel Prize in 1901. Röntgen failed to acknowledge Lenard’s assistance, leaving Lenard with a lasting grudge. Lenard finally secured a position where he could pursue his studies on cathode rays [[cvi]].

Lenard visited England in 1896, where J.J. Thomson (1856–1940), director of the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, was particularly interested in his work. Lenard claimed he sent some of his work to Thomson, who published it as his own.

“When he complained to Thomson, Thomson belatedly added a citation in a further publication but only to a later paper of Lenard’s, assuring Thomson’s claim of priority in the matter” [[cvii]].

In parallel with his research, Lenard was also a talented lecturer, “celebrated throughout Germany” [[cviii]]. Even Einstein’s girlfriend and soon to be wife, Mileva Marić (1875–1948), was a big fan, having attended Lenard’s lectures in Heidelberg [[cix]].

Lenard’s work earned him the appreciation of scientists throughout Germany, and in particular, from a young student then studying physics in Zürich. “I just read a most beautiful paper by Lenard about the generation of cathode rays (electrons) by ultraviolet light,” Einstein wrote to his then girlfriend, Mileva Marić in 1901. “Under the influence of this beautiful piece I am filled with such happiness and such joy, that you must absolutely have some of that too” [[cx]]. Einstein wrote in reply to Mileva’s letter informing him of her pregnancy, and would get to that subject later in the letter [[cxi]].

Lenard’s meticulous work on cathode rays and the photoelectric effect led to a Nobel Prize in 1905 [[cxii]]. It was these results Einstein explained in one of his 1905 papers, and which in 1922 led to the award of the 1921 Nobel Prize to Einstein [[cxiii]].

Soon after Einstein published his 1905 paper, the Nobel Laureate, Lenard, initiated a cordial correspondence with Einstein and sent him a reprint of his more recent experimental work. “Einstein replied that he had studied this new work ‘with the same feeling of admiration as your earlier works,’ and in a letter to a colleague he described Lenard as ‘not only a skillful master of his future, but a true genius’” [[cxiv]]. “Lenard did not accept Einstein’s interpretation of the photoelectric effect, and he continued to view the emission of electrons as some kind of resonance phenomenon that supposedly arises from Maxwell's equations” [[cxv], [cxvi]]. While the two disagreed, they nevertheless carried on a friendly correspondence [[cxvii]].

“Before the Great War, there was no trace of anti-Semitism in his [Lenard’s] interactions” [[cxviii]]. World War I sparked a change in Lenard’s views. Like many German academics, he blamed England, claiming England set France and Russia against Germany to weaken her continental rivals [[cxix]]. More recent scholarship aligns with this view [[cxx]]. Lenard had deeply personal reasons to lash out.

First, Philipp Lenard lost his son, “Werner, who died in February 1922, partially as a result of the malnutrition he suffered during the wartime blockade. He was the last of the family name” [[cxxi]].

Moreover, like many German patriots, Werner put all his wealth, including his Nobel Prize earnings, into German bonds rendered worthless by the hyperinflation engineered by the Weimar government [[cxxiii], [cxxiv]]. Times were tough (and would soon become even more difficult). In October 1920, Born wrote to Einstein:

In Lenard and Wien you see devils, in Lorentz an angel. Neither is quite right. The first two are suffering from a political illness, very common in our starving country, which is not altogether based on inborn wickedness. When I was in Göttingen just recently I saw Runge [probably mathematician Carl Runge (1856–1927)], reduced to a skeleton and correspondingly changed and embittered. It became clear to me then what is going on around here [[cxxv]].

In 1922, there was one man who became the focal point of dissatisfaction and anger, not only for Philipp Lenard, but also for far more radical Germans. That man was an assimilated Jew who regarded himself as fully German: Walther Rathenau (1867–1922), a German-Jewish industrialist who had helped organize the German war economy [[cxxvi]].

Now part of elite circles in Berlin, Einstein was friends with Rathenau, and often discussed politics [[cxxix], [cxxx]]. He introduced Rathenau to his friend, German-born Zionist, Kurt Blumenfeld (1884–1963), in hopes Blumenfeld could win Rathenau to the Zionist cause [[cxxxi]].

Blumenfeld argued “it was wrong for a Jew to presume to run the foreign affairs of another people” [[cxxxii], [cxxxiii]]. Rathenau disagreed, thinking that if Jews were to thoroughly assimilate as good Germans, it would reduce antisemitism [[cxxxiv]].

Rathenau accepted the position of Foreign Minister in the Weimar government in February 1922. He strongly supported German compliance with the Treaty of Versailles, whose reparations drove the hyperinflation [[cxxxv]]. He also negotiated the Treaty of Rappallo with the Soviet Union, further angering anti-communists [[cxxxvi]]. “This was denounced as the servile policy of a Jew; hence his assassination” [[cxxxvii]].

In June 1922, young nationalists ambushed Rathenau’s open car, shooting the foreign minister [[cxxxviii], [cxxxix]]. Two million Germans lined the streets of Berlin to pay tribute to Rathenau [[cxl]]. Philipp Lenard was not one of them.

Having previously called for the “elimination” of Rathenau, Lenard refused to observe the officially declared day of mourning ordered for Rathenau’s funeral [[cxlii], [cxliii]]. A crowd gathered, demanding he order the flag of the physics institute fly at half-mast and cease work for the day. The crowd – numbering in the hundreds and having been drenched with water from a second story firehose – broke into the institute and dragged Lenard into the union hall. Some suggested Lenard be thrown in the Neckar River, a detail featuring prominently in later accounts [[cxliv]]. Finally, Lenard was rescued, taken into protective custody to appease the crowd, and released later that night [[cxlv]].

The academic senate forbade Lenard from returning to the campus. His students compiled a 600-signature petition and got him reinstated. At the trial of those accused of leading the assault on the physics institute in April 1923, “the defense attorney, who was Jewish, managed to shift the blame for the event on Lenard’s provocation” [[cxlvi]].

Lenard ultimately received a reprimand from the university, but resigned in protest. The June 1922 assault by the pro-Weimar crowd became a cause célèbre and may have been the turning point for Lenard, where his animus toward Einstein in particular became hostility toward Jews in general [[cxlvii]].

Facing death threats, Einstein fled Berlin for Kiel on the Baltic coast. There, he continued working for the Anschütz company on gyrocompass technology. He testified on their behalf in a 1915 patent dispute [[cxlviii]], and continued on as a subject-matter expert and inventor [[cxlix]]. “Einstein’s ingenious idea of ensuring the frictionless rotation of a gyrocompass by locating a coil inside the sphere had been patented by the Anschütz firm on February 22, 1922, and represents his contribution to navigation” [[cl]]. German U-boats and most non-Anglo-Saxon naval vessels in WWII used an Anschütz gyrocompass including features invented and patented by Albert Einstein. He received a three-percent royalty on sales and license income until just before WWII [[cli]].

Lenard kept busy as well. He published a second edition of his anti-relativity text Äther und Uräther [Ether and Primordial Ether], placing in it “A Word of Admonishment to German Natural Scientists,” and he took his campaign against relativity to the public by reprinting it in nationalistic daily newspapers [[clii]].

In this he inveighed against “the confusion of concepts, hidden from those who knew nothing about race, surrounding Herr Einstein as a German scientist.” He got worked up about the “well-known Jewish characteristic of immediately shifting factual problems to the field of personal quarrel,” and he called for the cultivation of “sound German spirit.” Then “the alien spirit will yield all by itself, the spirit which emerges everywhere as a dark power and which is so clearly seen in anything that relates to the “relativity theory” [[cliii]].

Lenard and fellow anti-relativist physicist Ernst Gehrcke (1878–1960) also led a group of nineteen scientists who published a “Declaration of Protest” aimed at barring [Einstein] from the 1922 Naturforscher convention in Leipzig [[cliv]]. Einstein withdrew from public events, including the physics convention. Max von Laue delivered the keynote speech on relativity in his place [[clv]].

Lenard’s shift to racially-charged accusations backfired. “Heisenberg, who was present as a student in Leipzig, reported that the leaflets were distributed at the entrance to the lecture hall and how appalled he was that a respected physicist like Lenard was participating in this campaign” [[clvi]].

“Lenard’s blatantly anti-Semitic attacks on Einstein under these circumstances alienated him from his fellow physicists, and he received noticeably less support at Leipzig than he had at Nauheim” [[clvii]].

Even far-right nationalist physicists, such as Wilhelm Wien, were too intelligent in their field to make themselves and their anti-Semitism look foolish by arguing against relativity. That is why Lenard remained alone with a small handful of quacks. He irritated even politically like-minded colleagues not only by his opposition to relativity theory but also because he felt that on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the discovery of X-rays, he should have been honored as their codiscoverer.

The organized struggle against relativity theory virtually collapsed with the Leipzig convention. Certainly not a single “antirelativist” was appointed to any professorship of physics until 1933 – not even Johannes Stark, the Nobel laureate of 1919, who was soon to be Lenard’s only ally of any scientific repute. [[clviii]].

Einstein set out for Japan in October 1922, not long after the assassination [[clix], [clx]]. He’d been informally notified that he might want to swing by Stockholm in December, when Nobel Prizes were awarded. Einstein went to Japan, anyway. The November 1922 announcement that Einstein would be awarded the delayed 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics was a further setback for Lenard who had been campaigning against Einstein behind the scenes. Sidestepping the relativity controversy, the Nobel committee awarded the prize “for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.”

Not only did Einstein win the prize, but in an area Lenard had pioneered [[clxi]]. Lenard wrote a letter of protest to the Nobel committee [[clxii]] and publicly released his dissent in February 1923 [[clxiii]].

Lenard’s most significant ally was the 1919 Nobel Laureate in Physics, Johannes Stark (1874–1957). Like Lenard, Stark did not start out with any particular animus against Einstein in particular, or Jews in general.

Stark was an early adopter of the quantum hypothesis for light quanta [[clxvi], [clxvii]]. In 1907, Stark solicited Einstein to write a review article on special relativity for Jahrbuch der Radioaktivität and Elektronik (Journal of Radioactivity and Electronics), a journal Stark founded in 1904 and continued on as the editor [[clxviii]]. “Stark admired the theory, and this article helped cement Einstein’s dissatisfaction with his initial theory of special relativity,” [[clxix]] thus paving the way for General Relativity. They carried on a cordial correspondence, and Stark continued experimental investigations on the light quantum hypothesis to such an extent that Lorentz dubbed it the Einstein-Stark hypothesis [[clxx]]. In 1909 when Stark landed a professorship in Aachen (thanks to the support and intervention of Sommerfeld), he invited Einstein to join him as an assistant – an offer Einstein declined as he was then negotiating a position of his own in Zurich [[clxxi], [clxxii]].

Two incidents may have inspired Stark’s animus. The first was a priority dispute [[clxxiii]]:

Stark and Einstein independently worked out a result now referred to as the Stark-Einstein law, according to which the energy from absorbed electrons gives rise to chemical reactions. Stark contended that he was the rightful discoverer and, when Einstein dismissed Stark’s contention claiming to be above such trivial matters as priority, Stark was insulted, indignantly arguing that his work was first and simpler, and thereby better [[clxxiv]].

Ironically, years earlier, Stark mistakenly attributed E = mc2 to Planck, not realizing that Planck was citing Einstein. Einstein complained to him “I find it rather strange that you would not recognize my priority” [[clxxv]]. Stark was conciliatory and apologetic, and Einstein declared himself satisfied.

The second incident was in 1915, when he was passed over for a prestigious academic position he felt he deserved, in favor of Peter Debye (1884–1966), a student of Sommerfeld and associate of Einstein [[clxxvi]]. “Incensed, Stark railed against the powerful ‘Jewish and pro-Semitic circle’ of which he identified Sommerfeld as its ‘enterprising business manager’” [[clxxvii]].

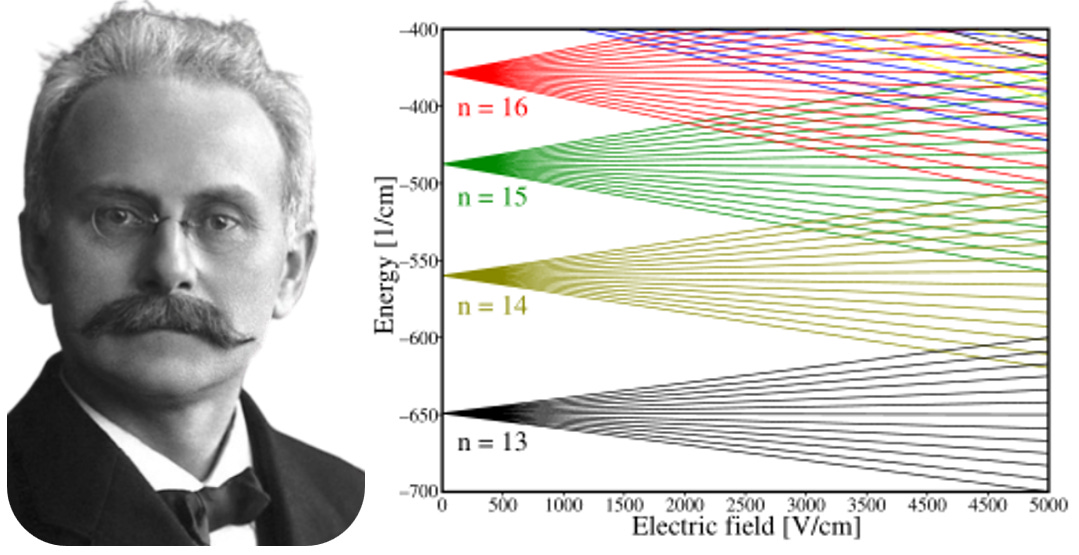

Stark’s second great discovery came in 1913, when he discovered the “Stark effect,” how an applied electric field causes spectral lines to divide into multiple closely spaced lines [[clxxviii], [clxxix]], work for which he was awarded the 1919 Nobel Prize [[clxxx]].

Stark’s careful experimental work provided clues into atomic behavior that helped shape the emerging quantum theory, but he thought “the Bohr quantum theory was of dubious value” [[clxxxi]]. In 1922, Stark’s monograph, The Present Crisis in German Physics, argued that “physics was being eclipsed by an abstract, degenerate form of theoretical physics” [[clxxxii]].

The increased significance of theoretical physics is also expressed in the fact that the number and scope of theoretical treatises in the physics journals had increased very much more than the number of treatises in which new phenomena, procedures, and devices are described or than improved measurements of physics factors are announced […] Indeed, the feeling of inferiority vis-à-vis theory seems to be gaining ground even among experimental physicists; […] Given these circumstances, it is probably justifiable to speak of an overgrowth of theory in current physics [[clxxxiii]].

Max von Laue (1879–1960) reviewed Stark’s 32-page treatise: “…the author pours his heart out and pontificates on everything he currently does not like in German physics. Unfortunately, this is quite a lot”. Von Laue declined to address the personal attacks Stark made, but otherwise summarized the arguments. He agreed that there was a crisis in physics. “…[I]t can only be overcome when science has found the answer to the quantum puzzle. There is no other remedy.” Von Laue concurred with Stark “that Germany should try to increase the amount of experimental research at the expense of theoretical work.” Writing in January 1923 as the hyperinflation was poised to go from very bad to even worse, von Laue pointed out, “…we all know that the current disproportion is mainly due to the predicament which our entire nation is in and that physicists are unfortunately not in the position to change it much.” Von Laue concluded, “All in all, we would have wished that this book had remained unwritten, that is, in the interest of science in general, of German science in particular, and not least of all in the interest of the author himself” [[clxxxiv]].

Stark allied with Wilhelm Wien, to rally opposition to the Berlin faction in the German Physical Society, creating a rival organization, but found himself out-maneuvered by Wien. Stark’s bureaucratic bickering and polemical attacks made him unpopular and hindered his ability to find a stable academic position [[clxxxv]]. After Stark’s porcelain manufacturing venture failed, the Nobel Laureate was unable to find another academic position during the Weimar period [[clxxxvi]]. Even in 1927 when Lenard wished to retire and appoint Stark as his successor, Lenard’s colleagues rebelled and blocked Stark’s appointment [[clxxxvii]].

Professional insults and great personal tragedy set Lenard on the path to National Socialism. Stark only required a distaste for the overabundance of abstract theory, being passed over for coveted academic positions [[clxxxviii]], and bitterness over professional setbacks and infighting. Stark’s answer to these slights was to take a different approach to his career, and, he declared, “as the National Socialist party entered the decisive struggle for power, I closed the doors of my physical laboratory and stepped into the ranks of the fighters behind Adolf Hitler” [[clxxxix]].

In November 1923 as the Weimar hyperinflation peaked and a US dollar was worth 4.2 trillion marks, Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) and General Erich Ludendorff (1865–1937), veteran of the failed 1920 Kapp Putsch, attempted a coup d’état in Bavaria. The Munich “Beer Hall Putsch” failed. A sympathetic judge issued a five-year sentence. Hitler served eight months in a comfortable prison cell where he wrote his political treatise, Mein Kampf [[cxc]].

On May 8, 1924, a week after Hitler was sentenced, “an article composed by Lenard and co-signed by Stark appeared in the Grossdeutsche Zeitung, a small, short-lived Pan-German newspaper in Bavaria” [[cxci]]. The two physicists recognized in Hitler and his associates:

…the same spirit we have ourselves always striven after and drawn forth in our work, so that it would be profound and successful — the spirit of restless clarity, honest in respect to the exterior world as well as the inner unity; the spirit which hates every work of compromise, because it is untruthful. It is indeed also the same spirit which we — as our ideal — have already recognized and revered early in the great researchers of the past, in Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Faraday. We admire and revere it in the same manner in Hitler, Ludendorff, Pohner, and their comrades; we recognize in them our closest spiritual relatives [[cxcii], [cxciii]].

There was much more in the same spirit.

Lenard had a deep reverence for the personalities and history of physics. He labored as carefully setting and rehearsing elaborate demonstrations for his students as he did in his own experimental work. Ironically, Lenard “failed to perceive that, by venerating the past and romanticizing physics, he had himself become one of the older ‘authorities’ against whom he had railed as a young researcher” [[cxciv]]. Sadly, Lenard made the fateful choice to place his reverence for physics in the service of National Socialism.

Science was another front in Hitler’s struggle. In 1921 he wrote, “Science, once our greatest pride, is today being taught by Hebrews, for whom ... science is only a means toward a deliberate, systematic poisoning of our nation’s soul and thus toward the triggering of the inner collapse of our nation” [[cxcv], [cxcvi]].

After he was released, Hitler remembered his early supporters. Hitler and his top associate, Rudolf Hess (1894–1987), paid a visit to Lenard in 1926 [[cxcviii], [cxcix]]. Lenard was in his seventies by the time Hitler came to power in 1933. He dedicated himself to writing histories and textbooks.

Lenard’s Great Men in Science, A History of Scientific Progress, provided biographical sketches of more than sixty scientists. “It is not often that one who, like Professor Lenard, has won for himself an assured place in the history of science, undertakes a systematic appreciation of the work of his predecessors, of the kind we have before us in this book” wrote one of his Jewish doctoral students in the preface to the 1933 English translation of Lenard’s historical treatise [[cc]]. There’s an allusion to his mentor, Heinrich Hertz, being “partly of Jewish blood,” but no overt attacks on Jewish physics [[cci]]. “In successive editions the racist terminology became more and more pronounced” [[ccii]].

A few years later in 1935, however, Lenard published his famed lectures in a four-volume science textbook, Deutsche Physik. In the introduction, he attacked the internationalism of science and upheld the superiority of German or Aryan physics, particularly contrasted against Jewish physics. He argued:

Nations of different racial mixes practice science differently…. Jews are everywhere; and whoever still contends that science is international today clearly means unconsciously Jewish science, which is, of course, similar to the Jews everywhere and is everywhere the same…. The Jew conspicuously lacks any understanding of truth beyond a merely superficial agreement with reality, which is independent of human thought. This is in contrast to the Aryan scientist’s drive, which is as obstinate as it is serious in its quest for truth…. Jewish ‘physics’ is therefore only an illusion and a degenerate manifestation of fundamental Aryan physics [[cciii]].

“It is fortunate for us that Lenard and Stark are no longer young,” a leading physicist confided to a colleague. “If they still had their youthful élan they would command what should be taught as physics” [[cciv]]. That didn’t keep Johannes Stark from trying, however.

In 1933, Stark finally achieved the presidency of the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology (PTR) in Berlin, a post he had unsuccessfully sought since 1922. Hitler’s Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick, granted him the appointment despite the unanimous objections of the scientific staff [[ccv]]. He sought to take control of all scientific publishing, reportedly telling an audience of publishers, “And if you're not willing, then I'll use force!” [[ccvi]]. Stark’s heavy-handed approach prompted a revolt.

When Planck and others nominated Stark for elevation to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in December 1933, von Laue acknowledged that Stark had been unfairly slighted for promotions and honors in the past. He successfully argued, though, that Stark’s election would be an unwelcome endorsement of Stark’s plan to gut theoretical in favor of experimental physics [[ccvii]]. By 1936, scientific opposition and political infighting had largely blocked Stark’s campaign. The last gasp of the Lenard-Stark influence on German physics came in 1939 when they successfully blocked Heisenberg from succeeding Sommerfeld in his prestigious Munich professorship [[ccviii]]. However – as previously described – Heisenberg’s mother enlisted Himmler’s mother to thwart Stark’s attempts to destroy Heisenberg’s career.

The Deutsche Physik movement and Stark’s political battles were mere sideshows, however, compared to the aggressive Nazi campaign to Aryanize German professional life.

In December 1932, Einstein left for a visit to America where he was the guest of Robert A. Milikan at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. He would never return to Germany [[ccx]].

On January 30, 1933, Hitler became Chancellor, and on February 27, 1933, the Reichstag Fire offered him a justification for crackdowns against communist subversion [[ccxi], [ccxii]]. Einstein left Pasadena and returned, not to Berlin, but to exile in Belgium where he renounced his German citizenship [[ccxiii]]. He submitted his resignation to the Prussian Academy of Sciences before the organization could expel him [[ccxiv], [ccxv]]. Nazis ransacked Einstein’s Berlin apartment multiple times, raided his summer cottage and confiscated his beloved sailboat under the excuse that it might be used for smuggling [[ccxvi]]. Lenard cheered the departure of Einstein, describing him as “the relativity Jew, whose mathematically cobbled theory ... is now gradually falling to pieces” [[ccxvii]].

In Berlin, the Nazi propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, led the proceedings, proclaiming “the end of the age of Jewish intellectualism” as fifty thousand books by Jews and other “traitors and degenerates” were burned [[ccxx], [ccxxi]].

Einstein joined a long list of German scientists and intellectuals fleeing the regime [[ccxxii]]. Jewish professors (including Max Born) were fired from their posts. At the renowned University of Göttingen, the mathematics and natural sciences schools lost more than half their faculty.

In 1934, the Nazi minister of education, Bernhard Rust, visited [the University of Göttingen]. At a banquet in his honor, Rust sat next to the famous old mathematician David Hilbert. Rust asked him if the institute had suffered from the expulsion of the “Jews and their friends.” Hilbert answered: “Suffered? It hasn’t suffered, Herr Minister. It no longer exists” [[ccxxiii]].

The 1933 Civil Service Law devastated German science. Physics suffered “a loss of at least 25 percent of its 1932-33 personnel, including some of the finest scientists in Germany” [[ccxxiv]].

By 1935, one in five scientists in Germany – one in four in the case of physicists – had been dismissed. And several (but by no means most) positions of power and influence had been filled by mediocre individuals promoted because of their obedience to the party. Moreover, the Nazis seemed to begin insisting not just on who did science, but on what science was done [[ccxxv]].

As a WWI veteran, Einstein’s friend Fritz Haber (1868–1934) was exempt from the mandate to fire Jewish civil servants. He resigned his position nevertheless in protest.

In a scientific capacity, my tradition requires me to take into account only the professional and personal qualifications of applicants when I choose my collaborators—without concerning myself with their racial condition. You will not expect a man in his sixty-fifth year to change a manner of thinking which has guided him for the past thirty-nine years of his life in higher education, and you will understand that the pride with which he has served his German homeland his whole life long now dictates this request for retirement [[ccxxvi]].

Haber’s resignation was accepted, and he threw himself into helping fellow Jews emigrate. He decided to relocate to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, but died of a heart attack on the way [[ccxxvii]]. Haber harvested bread from the air—and bombs. His synthesis of ammonia fed the world, but also kept German guns firing when nitrate imports failed. The Kaiser’s chemical Oppenheimer, he unleashed hitherto unimaginable horrors across the trenches of Ypres with his pioneering work in chemical warfare and toxic gases. And yet, the Third Reich, inheritor of the militarized science he helped to forge, terminated his story with exile and death.

Max Planck had spoken directly to Hitler on Haber’s behalf.

“I have nothing at all against the Jews as such,” Hitler insisted. “But the Jews are all communists and these are my enemies.”

Planck respectfully countered one must make distinctions between Jews.

"That's not right,” Hitler responded. “A Jew is a Jew; all Jews cling together like burrs. Wherever one Jew is, other Jews of all types immediately gather” [[i]].

Hitler refused to make distinctions. He was determined to be rid of them all, no matter their character, past record, or future potential to serve the Reich. Hitler was reported to have said:

Our national policies will not be revoked or modified, even for scientists. If the dismissal of Jewish scientists means the annihilation of contemporary German science, then we shall do without science for a few years!

The heavy metal band, Sabaton, explores Haber’s morally complicated career in “Father.”

In 1939 as war was about to break out in Europe, Einstein busied himself using his name to get emigration papers and rescue Jews from Germany, saying they were running “a little refugee office from” his “cluttered lawyer’s desk” [[ccxxviii]]. Mileva wrote him. She was reasonably safe from Nazi persecution as a Serbian Orthodox Christian. If Switzerland fell to the Nazis like neighboring Austria, however, their institutionalized half-Jewish son, Eduard, would never even make it to a camp. The eugenically-minded Nazis summarily shot mental patients. She beseeched Albert to save their son: “you can’t just leave him in the lurch” [[ccxxix]].

As far as is known, Einstein never replied. Eduard survived the war in Switzerland, succumbing to a stroke in 1965. “If I had been fully informed [apparently referring here to what he saw as a genetic mental illness in Mileva’s family], he [Eduard] would never have come into the world,” Einstein wrote to his other son, Hans Albert Einstein (1904–1973), who became a professor of civil engineering at the University of California, Berkely, and a leading expert on hydraulics [[ccxxx]].

Anyone who criticized Einstein “is either called an anti-Semite or someone who is too stupid to be able to grasp the theory of relativity, or both,” complained Gehrcke in 1921 [[ccxxxii]]. After the Nazis took over, however, it became “unworthy of a German to be the intellectual follower of a Jew,” according to Lenard. “Natural science, properly so called, is of completely Aryan origin, and Germans must today also find their own way out into the unknown. Heil Hitler!” [[ccxxxiii]].

This bitter political polarization made it unfashionable to question relativity even outside Germany. “Relativity is now accepted as a faith,” wrote R. A. Houstoun in his 1938 Treatise on Light. “It is inadvisable to devote attention to its paradoxical aspects” [[ccxxxiv]]. “One should respect an honest person even when he holds different views from one’s own,” Einstein declared [[ccxxxv]]. Many, including Einstein himself, failed to live up to this standard.

What of Einstein’s anti-relativity critics? After the war, Lenard – then in his eighties – was so frail he was never put on trial. Stark was adjudicated a “first rate offender” and sentenced to six years in prison, but that sentence was commuted to a thousand-mark fine [[ccxxxvi]].

What happened to Paul Weyland, the man whose 1920 anti-relativity campaign was so crucial in escalating the conflict between Einstein and the anti-relativists? After a notorious career of grifting and fraud across Europe and all the way to Latin America, he made his way back to Germany in 1939 where he was locked up in Dachau and other concentration camps until liberated by the US in 1945. He awarded himself a doctorate degree, and Dr. Paul Weyland (and his wife) emigrated to the US in 1948.

Weyland had one last card to play against his nemesis, however. While his naturalization was underway, he attempted to curry favor by denouncing Einstein as a communist to the FBI in 1953, prompting a massive investigation culminating in a 1500-page report. Weyland ultimately returned to Germany with his wife in 1967, where he died in 1972 [[ccxxxvii], [ccxxxviii]].

Conclusion

WWII created the foundational narrative of the present-day American Empire. The United States emerged as the sole surviving superpower with military ascendancy, global reach, economic supremacy, and an ideological and moral certainty that the United States was not only the preeminent champion of democracy but also had triumphed over the ultimate in geopolitical evil. This narrative catalyzed the permanent militarization of American society and the creation of the military-industrial-intelligence complex, particularly as the Soviet Union strove to defy American hegemony during the Cold War. The legacy of WWII was invoked to justify the United States exercising power around the world on behalf of a notion of “democracy” that did not always align with the most noble of motives. “It says here in this history book that luckily, the good guys have won every single time,” observed comedian Norm Macdonald (1959–2021). “What are the odds?”

The debate between advocates of Deutsche Physik and their opponents serves a similar role in framing our understanding of modern physics. Lenard and Stark make convenient cardboard- cutout villains: their extreme rhetoric of German superiority triumphantly refuted by the blinding light of a manmade Trinity in the New Mexico desert. This narrative makes it easy to dismiss any criticisms of relativity and quantum mechanics.

However, the story of relativity, and the story about to be told of quantum mechanics, were not primarily derivatives of Jewish thought – either from a racial or an ideological perspective. Ironically, the present-day interpretations of relativity and quantum mechanics alike were German science, principally the result of Mach’s positivism and Goethe’s Naturphilosophie. At worst, both were covered in a superficial veneer of so-called Jewish science — “purely formalistic, completely removed from observation, entirely concerned with the ways in which one should manipulate the symbols.”

The real Einstein did not live up to his cardboard cutout caricature as a hero, either. With a dark and deeply flawed personal character, he focused on himself at the expense of his family. He was prone to hypocrisy and adopting mutually contradictory positions. He dismissed dialectic criticism with rhetorical attacks, declaring all who disagreed with relativity were ignorant or antisemitic. He jealously guarded his own priority, yet expressed indifference to the priority claims of others, and he failed to acknowledge their contributions.

“The relationship between Einstein and the press is a case in which a scientist’s fame triumphed over the substance of his work,” declared physicist and popular science writer, Paul Halpern (1961– ), in the pages of Physics Today, the mainstream magazine for professional physicists [[i]]. Einstein himself concurred, saying that “he had been given a publicity value which he did not earn” [[ii]]. That publicity was a double-edged sword. “The newspapers have mentioned my name too often, thus mobilizing the rabble against me,” Einstein explained in a 1922 letter to Max Planck [[iii]].

For all his faults, however, Einstein’s narrative has a redemption arc. His Mach-inspired advocacy for an observer-first approach to physics led to relativity. Yet, he was repelled by the sight of Goethe’s acolytes taking his philosophical premises to their logical extremes: “Perhaps I did use such a philosophy earlier, and also wrote it, but it is nonsense all the same.” As we shall see, once we have entered the quantum realm, it was Einstein who pointed the way toward a possible resolution to quantum paradoxes.

First however, having cleared the way by dispelling the competing counter narratives obscuring our understanding of relativity, we are ready to take a closer look at experimental validation and open questions.

Next time: 5.2.10: Experimental Validation & Open Questions

Enjoyed the article, but maybe not quite enough to spring for a paid subscription?

Then click on the button below to buy me a coffee. Thanks!

Full Table of Contents [click here]

Follow Online:

You may follow me online in other places as well:

Telegram: 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕔𝕫𝕒𝕣'𝕤 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕥𝕣𝕖𝕒𝕞

Gab: @aetherczar

Twitter: @aetherczar

Amazon: Hans G. Schantz

References

[[i]] Einstein, Albert, “Anti-Semitism. Defense through Knowledge,” after 3 April, 1918. Collected Papers, vol. 7, p. 156.

[[ii]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, pp. 153-154.

[[iii]] “Professor Albert Michelson 79 Year Old Jewish Scientist Has Nervous Breakdown Because of Overwork,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, vol. XII, no. 78, 6 April, 1931, p. 3. See: https://www.jta.org/archive/professor-albert-michelson-79-year-old-jewish-scientist-has-nervous-breakdown-because-of-overwork Note, Wikipedia lists a reference I was unable to validate. See also: https://web.archive.org/web/20160203232123/https://www.aip.org/history/exhibits/gap/Michelson/Michelson.html

[[iv]] Caracciolo, Alberto, “Una Diaspora Da Trieste: I Besso Nell’Ottocento,” Quaderni storici, Vol. 18, No. 54 (3), Ebrei in Italia (dicembre 1983), pp. 897-912. See: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43776886

[[v]] Pais, Abraham, Niels Bohr’s Times: In Physics, Philosophy, and Polity, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993, pp. 32-36.

[[vi]] German physicist Pascual Jordan. 1920s. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pascual_Jordan_1920s.jpg See also: https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/online/9149/Pascual-Jordan

[[vii]] Born, Max, Physics in my Generation, London: Pergamon Press, 1956, p 6.

[[viii]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 145.

[[ix]] Seeger, Raymond, J., “Heisenberg, Thoughtful Christian,” Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation, December 1985, pp. 231-232.

[[x]] Cassidy, David Charles, Uncertainty: the life and science of Werner Heisenberg, New York: W.H. Freeman & Co., 1993, p. 13.

[[xi]] Jungnickel, Christa, and Russell McCormmach, Intellectual Mastery of Nature: Theoretical Physics from Ohm to Einstein Volume 2: The Now Mighty Theoretical Physics 1870-1925, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, p. 363

[[xii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 579.

[[xiii]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, pp. 153-154.

[[xiv]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 515

[[xv]] Copies are hard to find. This one was available online for € 77: https://tinyurl.com/4rjsjkam

[[xvi]] German physicist Pascual Jordan. 1920s. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pascual_Jordan_1920s.jpg See also: https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/online/9149/Pascual-Jordan

[[xvii]] Schroer, Bert, “Pascual Jordan, his contributions to quantum mechanics and his legacy in contemporary local quantum physics,” 15 May, 2003. See: https://arxiv.org/pdf/hep-th/0303241

[[xviii]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 154.

[[xix]] Born, G. V. R., “The wide-ranging family history of Max Born,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society, vol. 56 no. 2, 2002, pp. 219–262. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2002.0180

[[xx]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 154.

[[xxi]] Dahn, Ryan, “Nazis, émigrés, and abstract mathematics,” Physics Today, vol. 76, no. 1, 1 January 2023, pp. 44–50. doi: 10.1063/PT.3.5158.

[[xxii]] Enrico Fermi and his family pose for photo outdoors, possibly upon arrival in the USA. Catalog ID Enrico Fermi G12. Used with permission from AIP. See: https://repository.aip.org/fermi-and-family

[[xxiii]] Portrait of Wolfgang Pauli. Catalog ID Pauli Wolfgang A5. Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Gift of Karl von Meyenn. See: https://repository.aip.org/portrait-wolfgang-pauli

[[xxiv]] Schücking, Engelbert L., “Jordan, Pauli, Politics, Brecht, and a Variable Gravitational Constant, Physics Today, vol. 52, no. 10, 1999, pp. 26-31. See: https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/52/10/26/410663/Jordan-Pauli-Politics-Brecht-and-a-Variable

[[xxv]] Kragh, Helge, “Pascual Jordan, Varying Gravity, and the Expanding Earth. Physics in Perspective,” Physics Perspectives, vol. 17, no. 2, 21 April, 2015, pp. 107–134. doi:10.1007/s00016-015-0157-9

[[xxvi]] Segrè, Emilio, From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980, pp. 158-159.

[[xxvii]] Segrè, Emilio, From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980, pp. 200-222.

[[xxviii]] Segrè, Emilio, From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980, pp. 149-153.

[[xxix]] Segrè, Emilio, From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980, pp. 160-165.

[[xxx]] Farmelo, Graham, The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Mystic of the Atom, pp. 253, 256, 257, 284. Dirac married Margit “Manci” Wigner (1902–1984), sister of Hungarian-American physicist Eugene Wigner (1902-1995), in London in 1937.

[[xxxi]] Fermi, Laura, Atoms in the Family, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954, p. 56.

[[xxxii]] Segrè, Emilio, From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980, p. 206.

[[xxxiii]] Segrè, Emilio, From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980, p. 213.

[[xxxiv]] Segrè, Emilio, From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980, pp. 160-165.

[[xxxv]] Enz, Charles P., No Time to be Brief, Oxford: Oxfoird University Press, 2002, pp. 1-19

[[xxxvi]] Pais, Abraham, Niels Bohr’s Times: In Physics, Philosophy, and Polity, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911, p. 161.

[[xxxvii]] Jungnickel, Christa, and Russell McCormmach, Intellectual Mastery of Nature: Theoretical Physics from Ohm to Einstein Volume 2: The Now Mighty Theoretical Physics 1870-1925, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, p. 351-354.

[[xxxviii]] Pais, Abraham, Niels Bohr’s Times: In Physics, Philosophy, and Polity, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911, p. 161.

[[xxxix]] Bernstein, Jeremy, Hans Bethe, Prophet of Energy, New York: Basic Books, 1980, p. 8.

[[xl]] Davies, Mansel, “Peter Joseph Wilhelm Debye. 1884-1966,” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, vol. 16, no. 0, 1970, pp. 175–232. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1970.0007.

[[xli]] Beyerchen, Alan D., Scientists under Hitler: Politics and the Physics Community in the Third Reich, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977, p. 158.

[[xlii]] Ball, Philip Ball, Serving the Reich: The Struggle for the Soul of Physics Under Hitler, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014, pp. 100-101.

[[xliii]] Photograph of Nobel Prize laureates Paul Dirac, Werner Heisenberg, and Erwin Schrödinger in 1933. See: https://picryl.com/media/nobelpristagare-1933-fran-vanster-paul-dirac-werner-heisenberg-och-erwin-schrodinger-4a693a

[[xliv]] Cassidy, David Charles, Uncertainty: the life and science of Werner Heisenberg, New York: W.H. Freeman & Co., 1993, pp. 385-386. Quoting Himmler to Heydrich, 21 Jul 1938 (facsimile of certified copy in Alsos, p. 116; transcript in “Research: Ahnenerbe, Heisenberg, Werner,” BDC Berlin). Himmler’s phrase “tot zu machen” is sometimes translated as “to silence.” It may also mean “to kill” (literally: “to make dead”).

[[xlv]] Beyerchen, Alan D., Scientists under Hitler: Politics and the Physics Community in the Third Reich, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977, pp. 159-160.

[[xlvi]] Goudsmit, Samuel A., Alsos: The Failure in German Science, London: Sigma Books, 1947, pp. 114-119.

[[xlvii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 97-98.

[[xlviii]] Photograph of Sommerfeld, Arnold, 1868-1951. Credit Line: ‘Voltiana,’ Como, Italy - September 10, 1927 issue, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. See: https://repository.aip.org/portrait-arnold-sommerfeld-5

[[xlix]] Photograph of Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (1853–1928). Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archive. See: https://repository.aip.org/hendrik-lorentz-3

[[l]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 202.

[[li]] Pais, Abraham, Niels Bohr’s Times: In Physics, Philosophy, and Polity, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911, p. 161.

[[lii]] Hentschel, Klaus (ed.), Ann M. Hentschel, Editorial Assistant and Translator, Physics and National Socialism An Anthology of Primary Sources, Boston: Birkhauser Verlag, 1996, p. lxxv-lxxvi. See also Stark: ‘White Jews’ in Science [July 15, 1937] Source: “‘Weibe Juden’ in der Wissenschaf,” Das Schwarze Korps, issue no. 28, July 15, 1937, p. 6; reprinted, e.g., in Sugimoto [1989], p. 126. (Anonymous article). Reprinted on pp. 152-157.

[[liii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 97-98.

[[liv]] The BORN-EINSTEIN Letters: Correspondence between Albert Einstein and Max and Hedwig Born from 1916 to 1955 with commentaries by MAX BORN, Translated by Irene Born, New York: Macmillan, 1971, Letter #81, pp. 148-149. This is the famous “God doesn’t play dice” letter about which I will have much more to say presently.

“We have become Antipodean in our scientific expectations,” Einstein wrote to Born. “You believe in the God who plays dice, and I in complete law and order in a world which objectively exists, and which I, in a wildly speculative way, am trying to capture.”

[[lv]] The BORN-EINSTEIN Letters: Correspondence between Albert Einstein and Max and Hedwig Born from 1916 to 1955 with commentaries by MAX BORN, Translated by Irene Born, New York: Macmillan, 1971, Letter #83, pp. 155-157.

[[lvi]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 97-98.

[[lvii]] Fölsing, A., Albert Einstein, Eine Biographie, Frankfort: Suhrkamp, 1993, p. 791. Cited by Ohanian, p. 4.

[[lviii]] Seelig, Carl, Albert Einstein: A Documentary Biography, translated by Mervyn Savill, London: Staple Press Limited, 1956, pp. 125-126. The story was told by James Francks who laughed at his own story to the listeners at Leiden. “The Ehrenfest couple shared Professor Franck’s laughter. Lorentz, however, remained serious and after a few moments’ silence added: ‘‘Well, yes, Einstein is certainly in a position to argue on such lines.” Seelig, Einstein, pp. 125-126.

[[lix]] Photograph of Werner Heisenberg, German theoretical physicist and Nobel prize winner (1901–1976). Courtesy, Friedrich Hund. “Das Foto nahm mein Vater 1926 auf. Das Original stammt aus seinem Nachlass und ist in meinem Besitz.” See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heisenberg,Werner_1926.jpeg

[[lx]] From left to right: W. Nernst, A. Einstein, M. Planck, R.A. Millikan and von Laue at a dinner given by von Laue on 12 November 1931 in Berlin. See: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nernst,_Einstein,_Planck,_Millikan,_Laue_in_1931.jpg

[[lxi]] Arthur Zajonc, Catching the Light: The Entwined History of Light and Mind, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 246

[[lxii]] Heisenberg, Werner, Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversations, New York: Harper & Row, 1971, pp. 62-69. It’s a long account, but well worth tracking down.

[[lxiii]] Photograph of Werner Heisenberg, German theoretical physicist and Nobel prize winner (1901–1976). Courtesy, Friedrich Hund. “Das Foto nahm mein Vater 1926 auf. Das Original stammt aus seinem Nachlass und ist in meinem Besitz.” See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heisenberg,Werner_1926.jpeg

[[lxiv]] Charles Scolik - Christian Lunzer (Hrsg.): Wien um 1900 - Jahrhundertwende, ALBUM Verlag für Photografie, Wien 1999. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Mach#/media/File:Mach,_Ernst_(1905).jpg

[[lxv]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, pp. 24-25.

[[lxvi]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 47.

[[lxvii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 97-98.

[[lxviii]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 467.

[[lxix]] Bernstein, J., “Einstein and the existence of atoms,” American Journal of Physics, vol. 74, no. 10, October 2006, pp. 863-872. His reference appears spurious, so I was unable to confirm the quote. Caveat lector.

[[lxx]] The BORN-EINSTEIN Letters: Correspondence between Albert Einstein and Max and Hedwig Born from 1916 to 1955 with commentaries by MAX BORN, Translated by Irene Born, New York: Macmillan, 1971, Letter #81, pp. 148-149.

[[lxxi]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, pp. 460-461.

[[lxxii]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, pp. 460-461.

[[lxxiii]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, pp. 460-461.

[[lxxiv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, pp. 460-461.

[[lxxv]] Holton, Gerald, “Mach, Einstein, and the Search for Reality,” collected in Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought: Kepler to Einstein, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973, p. 245.

[[lxxvi]] Hubisz, John L., “Book Reviews,” The Physics Teacher, vol. 52, April 2014, p. 255.

[[lxxvii]] Davies, M., “Peter Joseph Wilhelm Debye. 1884-1966,” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 16(0), 1970, pp. 175–232. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1970.0007

[[lxxviii]] Frank, Philipp, Einstein: His Life and Times, New York: Alfred Knopf, 1947, p. 233.

[[lxxix]] Duhem, Pierre, The Aim and Structure of Physical Theory, New York: Antheneum, 1962, pp. 69-71.

[[lxxx]] Faust und Mephisto. Öl auf Leinwand. 80 x 65 cm. Rechts oben signiert. ~1900. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anton_Kaulbach_Faust_und_MephistoFXD.jpg

[[lxxxi]] Duhem, Pierre, The Aim and Structure of Physical Theory, New York: Antheneum, 1962, pp. 69-71.