Part 1 introduced the legendary public relations pioneer Edward L. Bernays who plays an important role in today’s post. This piece describes how Einstein came to America in 1921 as a member of a Zionist fundraising mission. Divisions between assimilationist Jews and more radical Zionist Jews had the unintended effect of shifting the focus away from the mission and placing the spotlight firmly on Einstein himself, launching his career as an American icon.

The publicity unfolded in the kind of “events and circumstances” that were the hallmark of a Bernays campaign. While there’s circumstantial evidence Bernays may have been involved, the evidence isn't conclusive. Adding to the conflict and drama, Einstein himself held views with respect to the Zionist movement that today might be termed “antisemitic.”

Einstein in particular and relativity in general were an important but small piece of the overall cultural milieu that emerged in the 1920s: an enshrinement of science in place of religion, but a science whose supposed truths included the principle that no truth was possible. Read on!

A Trip is Planned

As 1920 ended and 1921 began, Einstein sought an opportunity for economic independence. The worst was yet to come, but German currency was already beginning to be devalued, and the obligations of supporting his ex-wife and children in expensive Switzerland remained the same. Einstein accepted a position as a professor at Leiden in February 1920, long before the tumultuous anti-relativity debates of the fall of that year. He was only able to occupy that chair in October 1920, after the protests, because of a long delay in securing Dutch government permission to finalize the appointment. “The explanation involves a case of mistaken identity with Carl Einstein, Dadaist art, and a particular Dutch fear of revolutions” [[i]].

Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (1853–1928) had asked Einstein to discuss publicly his latest views on the existence of the æther. Einstein, who previously argued for the æther’s nonexistence, now declared, in his inaugural lecture, that an æther exists, and that “space without æther is unthinkable” (as previously noted) [[ii]].

Einstein approached U.S. universities about a potential 1921 lecture tour, demanding $15,000 in the more stable U.S. currency to speak at Princeton and Wisconsin [[iii]]. This was not an entirely unreasonable expectation given Bernays had been involved in $10,000 lecture plans for the Austrian-Jewish psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) in 1920 [[iv]]. When the American universities declined, he made alternate plans for 1921 [[v]]. Einstein scheduled another visit to Ehrenfest and Lorentz and more lectures at Leiden, and he would attend the third Solvay Conference in Brussels as the only German invited. These well-laid plans were about to be upset by a decision that would change the course of Einstein’s life.

An Invitation to America

While World War I was still raging on, Chaim Weizmann (1874–1952) laid the cornerstone for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in July 1918 [[viii], [ix]]. Weizmann, who was director of the chemical research laboratories of the British Admiralty during the war, pioneered the use of biological reactions in chemical engineering – figuring out how bacteria could be used to breakdown chemicals and yield desired derivatives in mass quantities for the British war effort [[x], [xi]]. After the British announced their support for “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, Weizmann led the English Zionist Commission mission to Palestine a few weeks later [[xii]].

Einstein is said to have co-founded the Hebrew University of Jerusalem with Weizmann in July 1918 [[xiii]]. It is unlikely the two enemy nationals were colluding with each other while their nations’ armies were engaged in trench warfare in France, however. German-born Zionist, Kurt Blumenfeld (1884–1963), recruited Einstein to the Zionist cause in early 1919 [[xiv], [xv]]. “I thank you belatedly for having made me conscious of my Jewish soul,” he wrote to Blumenfeld decades later [[xvi]]. “Although Einstein did not formally join any organization, he endorsed the notion of a Hebrew University in Jerusalem” [[xvii]]. In early 1921, Blumenfeld called upon Einstein to make his rhetoric reality and turn his theory into practice.

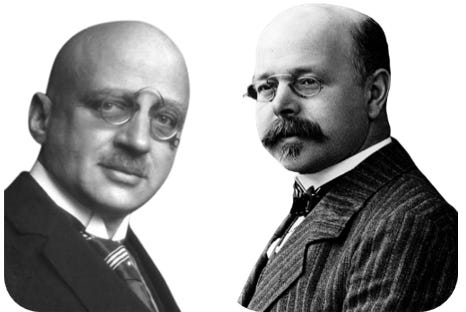

Blumenfeld prevailed upon Einstein to drop his plans and accompany Weizmann, now head of the World Zionist Organization, on a promotional tour to the U.S. to raise funds for the Hebrew University in Jerusalem [[xx], [xxi]]. Einstein’s decision caused consternation in Germany and with longtime friends like Fritz Haber (1868–1934) and Walther Nernst (1864–1941).

Einstein’s Friends Feel Betrayed

Fritz Haber earned the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918 for his invention of the Haber-Bosch process which synthesized ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen gases. His discovery fed millions through its application to fertilizer, and killed millions more through its application to manufacturing explosives. He further put his talents to work for the Kaiser, developing chlorine and other poisonous gases including the infamous Zyklon B. His wife, Clara, died by suicide using his Army pistol. She was rumored to be in despair by the war and her husband’s role in it [[xxii]]. Haber was of Jewish heritage but thoroughly assimilated.

Einstein and Haber were close friends, though they were radically different in character and in their politics. Einstein was a cosmopolitan bohemian, Haber a stiff and disciplined German patriot. Einstein was a conscious Jew; Haber converted to Christianity. Even so, they formed a tight partnership, sustaining each other as scientists and as Jews [[xxiii]].

Haber saw Einstein’s actions as “fraternization with the enemy” and feared it would reflect poorly on the loyalty of German Jews to their Fatherland [[xxiv]]. “What you do, you do not only with an effect on yourself” [[xxv]].

To the whole world you are today the most important of German Jews. If at this moment you demonstratively fraternize with the British and their friends, people in this country will see this as evidence of the disloyalty of the Jews. Such a lot of Jews went to war, have perished, or become impoverished without complaining, because they regarded it as their duty. Their lives and death have not liquidated anti-Semitism, but have degraded it into something hateful and undignified in the eyes of those who represent the dignity of this country. Do you wish to wipe out the gain of so much blood and suffering of German Jews by your behavior? You will certainly sacrifice the narrow basis upon which the existence of academic teachers and students of the Jewish faith at German universities rests [[xxvi]].

Einstein’s political views had often exasperated his friends and colleagues. After World War I, Russian and Polish Jewish refugees, fleeing hunger, hardship, and persecution surged into Berlin. Assimilated German Jews were embarrassed by their impoverished relatives, and Nationalist Germans wanted them deported. Einstein however, declared his solidarity with his “tribal companions,” argued it would be barbaric to expel them, and it would hurt German attempts to regain lost moral credit abroad. Einstein suggested Jewish refugees should be helped until they could have a homeland in Palestine. Despite their admiration for him, German Jews found Einstein’s politics “as incomprehensible as his theories” [[xxvii]].

Walther Nernst (1864–1941) collaborated with Haber on wartime chemical weapons research, and he won the 1920 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on thermodynamics. Nernst had accompanied Planck to Zürich in 1913 to recruit Einstein to Berlin [[xxviii], [xxix]], and had loyally supported Einstein in the recent dispute with Weyland and the anti-relativists [[xxx]]. Nernst was similarly furious with Einstein’s breach of solidarity [[xxxi]], and he had good reason to feel betrayed.

The distinguished chemist had collaborated with the Belgian industrialist, Ernest Solvay (1838–1922), to kick off the renowned Solvay Conference in 1911 [[xxxiii]]. Amid lingering post-war tensions, Nernst, himself, and all other German scientists were persona non grata at the very conference Nernst had helped found. Einstein was the only German invited. His ambiguous Swiss ties and well-known pacifism made it easier for the Solvay Conference organizers to invite him, despite his German citizenship [[xxxiv]]. And now, Einstein was throwing away his opportunity to represent Germany by declining the invitation.

Furthermore, Germans were suffering under the crushing burden of war reparations and a weak central government, while Einstein sailed on ships under the flags of their recent enemies, hobnobbed with the foreigners who had killed their sons and reduced them to debtors, and attacked German Nationalists in interviews with foreign reporters [[xxxv]].

“Here there is considerable outrage,” Einstein wrote to Ehrenfest, “which, however leaves me cold. Even the assimilated Jews are lamenting or berating me” [[xxxvi]]. Einstein was not sympathetic. “'I have always been annoyed by the undignified assimilationist cravings and strivings which I have observed in so many of my [Jewish] friends…. These and similar happenings have awakened in me the Jewish national sentiment” [[xxxvii]].

And so, Albert and Elsa Einstein departed from Holland on March 21, 1921 for America [[xxxix]] in the company of Chaim Weizmann and a couple other Zionist leaders for the visit that would make Einstein a scientific superstar in the United States. Before the visit Einstein was hardly known. He would depart a household name.

A Warm Welcome

A vast and heavily Jewish crowd assembled to greet the party at the dock, some 5000 strong [[xl]].

Thousands of spectators, along with the fife-and-drum corps of the Jewish Legion, were waiting in Battery Park when the mayor and other dignitaries brought Einstein ashore on a police tugboat. The crowd, waving blue-and-white flags, sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” and then the Zionist anthem, “Hatikvah.” …their motorcade wound through the Jewish neighborhoods of the Lower East Side late into the evening. “Every car had its horn, and every horn was put in action,” Weizmann recalled [[xli]].

But who were they there to see? In the Jewish, Yiddish-language newspapers that motivated the huge turnout, the attention was on Weizmann and the Zionist mission, not on Einstein [[xliii]]. Another clue to the crowd’s interest is evident in the famous photo of Einstein riding in a motorcade. A closer look shows that the crowd’s attention is focused on the following vehicle, not on Einstein [[xliv]].

The English-language press told a different story. Their reporters were unfamiliar with Zionism and had never heard of Weizmann. They were familiar with Einstein, however. In their reporting, Einstein was the focus, and the reporters naturally presumed the enormous crowd had waited patiently to see him [[xlv]]. That fortunate misunderstanding made it possible for Einstein’s considerable charisma to work its charm on reporters.

Although he professed a dislike for reporters, Einstein got along with them very well.

He was not a haughty, aloof European looking down on boorish Americans. Rather, he was modest, humorous and most of all, informal. Furthermore, he was good copy - he gave quotable quotes….

Besides his easy-going manner, which so surprised everyone, there was his actual physical appearance, which was also reassuring. He did not look like a haughty European scientist. The first photographs that appeared of him in newspapers in April of 1921 showed him standing in an ill-fitting coat, holding a violin, and smiling in a bemused way. It was not at all a frightening picture, and, highlighting the reassuring aspect of Einstein's appearance, was the fact that his pictures often had him standing next to Chaim Weizmann, the leader of the Zionist delegation, under whose auspices Einstein had come to America. Weizmann, who had a goatee and was impeccably dressed, was the embodiment of the very formal European professor [[xlvi]].

As Einstein’s biographer, Walter Isaacson (1952 – ) noted, Einstein’s “trip to America triggered the kind of mass hysteria that would greet the Beatles four decades later” [[xlvii]].

The Public Relations Behind the Visit?

The Beatles are alleged to have been “brought to the United States as part of a social experiment which would subject large population groups to brainwashing of which they were not even aware” [[xlviii], [xlix]]. Was there a similar effort made to popularize Einstein? Intriguingly, there is some circumstantial evidence to that effect. The enormous crowd greeting the Zionist party was surely an “event and circumstance which newspapers are compelled to notice as news,” the hallmark of an Edward Bernays publicity campaign, and a frequent means by which he accomplished his publicity magic. But was there a connection of some kind between Edward Bernays and these events? The answer is, “yes.” Bernays was close to Chaim Weizmann.

Bernays did not have a formal client-counsel relationship with Weizmann. Their bond was social, but Bernays is acknowledged to have “counseled” Weizmann in the 1920s [[l]]. About what, the record isn’t clear. According to one account, Weizmann offered Bernays the job of first foreign secretary of the future Jewish state of Israel in exchange for his services, an offer Bernays declined [[li], [lii]]. That offer would be renewed by Golda Meir decades later [[liii]] “I greatly respected Weizmann,” Bernays declared, “but I was not in sympathy with his goal” [[liv]]. There is an opportunity for Bernays’ hand to have been at work.

Why might such a project have been of interest to Bernays? Novelist Theodore Dreiser (1871–1945) was a big fan of the work of Charles Fort (1874–1932) – a researcher and writer who investigated and cataloged anomalous “Fortean” phenomena at odds with conventionally understood science. Wanting to keep one of their top writers happy, Dreiser’s publisher agreed to print five hundred copies of Fort’s The Book of the Dammed in 1919 [[lv]].

Fort’s treatise compiled facts that were “damned” or ignored by modern science because they conflicted with accepted scientific principles. His thesis was that mainstream scientists are conformists unwilling to search for truths contrary to accepted wisdom. His publisher turned the promotion job over to their publicist, Edward Bernays, who offered the selling point: “For Every Five People Who Read It Four Will Go Insane!” The book went on to be a spectacular success and saw not only a couple of sequels, but also the formation of the Fortean Society to celebrate and extend upon their namesake’s work [[lvi]]. Bernays happily promoted the work of Charles Fort because, as he wrote in his memoirs, it “challenged the fetish of the logic of science” [[lvii]].

In addition to attacking science, Bernays boosted feminism and sexual liberation. His first big theatrical success was promoting Damaged Goods, a “dull and almost unendurable” play about a man with syphilis who marries and fathers a syphilitic child. The play attacked prevailing standards of prudery at a time when public discussion of sexually transmitted disease was taboo [[lviii]].

Thanks to Bernays, and with the educational mission of the play endorsed by the likes of John D. Rockefeller Jr., Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt Sr., Mr. and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, and many others, [[lix]] “Damaged Goods was a cause célèbre before the curtain rose” [[lx]]. In the words of a 1913 editorial, the play made it strike “sex-o-clock in America” [[lxi]].

Bernays also boosted the work of his uncle, Sigmund Freud, in the 1920s. “Without him… Sigmund Freud’s work might not have been translated for American readers for another decade” [[lxii]]. “Freud’s name in the 1920s became inextricably linked with the idea of social reform as well as sexual freedom” [[lxiii]].

Bernays was a social activist, and his political and social goals were often a complementary factor in the campaigns and causes he promoted. Bernays had the means – his superb skill at coordinating events and circumstances. He had the opportunity – his personal relationship with Weizmann. He had potential motives – his desire to challenge the “fetish of the logic of science” by promoting Einstein’s revolutionary ideas. Finally, although Bernays “pretended to have no special bond with those trying to start a Jewish state” he “never truly divorced himself from Jewish culture” [[lxvi]]. There’s a strong circumstantial, albeit not conclusive, case for his involvement.

Mitigating against the hypothesis that Bernays was involved is the fact that he never bragged about the details of what he did on Weizmann’s behalf. We can only wonder and speculate. Bernays was never well-liked by fellow professionals because of his ceaseless self-promotion and endless lobbying for the status of father and creator of their profession [[lxvii]]. One declared, “…he had only one client and that was Edward L. Bernays” [[lxviii]]. Bernays often violated client confidentiality to seek credit for his accomplishments [[lxix]]. “…[A]s far back as 1930, he was naming clients for reporters writing sympathetic stories” [[lxx]]. “The amount of material written by and about Edward L. Bernays is, to put it mildly, voluminous, a result of his unceasing self-promotion and his longevity” [[lxxi]]. Bernays’ fame was in part due to the fact “…he always got the last word because he outlived contemporaries…” [[lxxii]].

Einstein Outshines His Own Mission

Whether Bernays was directly involved or not, the publicity campaign surrounding the arrival of the Zionist mission to America was stunningly successful, if not exactly in the way the organizers may have intended.

The campaign propelled Einstein and his personal scientific fame ahead of the Zionist mission he had come to America to represent, at least from the perspective of the mainstream press. “Thousands Greet Famous Scientist” proclaimed headlines across the country. “Professor Einstein Here, Explains Relativity,” was the New York Times headline. “Thousands Wait Four Hours to Welcome Theorist and his Party to America,” the coverage declared in a subheading. “He looked like an artist,” the New York Times reported. “But underneath his shaggy locks was a scientific mind whose deductions have staggered the ablest intellects of Europe” [[lxxiv]].

While Weizmann solicited funds for the Zionist cause, Einstein delivered lectures in German that packed the Metropolitan Opera House and other venues. After three weeks of lectures and receptions in New York, Einstein travelled to Washington, where he met President Harding [[lxxv]].

Einstein did not receive the $15,000 he originally sought, but he nevertheless delivered a weeklong series of scientific lectures at Princeton University for a more modest fee. He accepted an honorary degree “for voyaging through strange seas of thought.” Princeton agreed to publish his lectures as a book, The Meaning of Relativity, and offered a royalty of 15% [[lxxvi]].

These lectures illustrate Einstein's expository writing at its best, and they give a good, concise introduction to special and general relativity. However, the lectures repeat many of the mistakes found in his earlier work, such as the mistake about the meaning of synchronization by light signals, the mistake about the proof of E = mc2, and the mistake about the Principle of Equivalence [[lxxvii]].

Einstein’s lectures included more than 125 equations scribbled on the blackboard while he spoke in German. One student told a reporter, “I sat in the balcony, but he talked right over my head anyway” [[lxxviii]].

During a reception for Einstein at Princeton University, someone informed him that Dayton Clarence Miller (1866–1941) at the Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, Ohio had repeated the Michaelson-Morley experiment and detected motion through the æther [[lxxix], [lxxx], [lxxxi]]. “Raffiniert ist der Herrgott aber boshaft ist Er nicht,” Einstein declared. This is often translated as “The Lord is subtle, but not malicious,” and inspired the title of the Einstein biography, Subtle is the Lord, by Abraham Pais (1918–2000). “As a German speaker, Pais should have known better. The German word raffiniert has a rather negative connotation; its correct translation is ‘cunning’ or ‘crafty,’ and thus, ‘The Lord is cunning, but not malicious’” [[lxxxii]]. Einstein’s remark was eventually carved in stone in the fireplace in the new mathematics building at Princeton.

Tensions Within the American Jewish Community

Just as Einstein and his Zionist colleagues had opened fissures within the community of assimilated Jews in Germany, so also were similar tensions reaching a breaking point among the Jewish community in America. In Boston, Einstein was invited to visit Harvard, but not to give a lecture. Einstein’s biographer, Walter Isaacson, explains the snub:

He [Einstein] found himself caught in a battle between ardent European Zionists led by Chaim Weizmann, who was with Einstein on the trip, and the more polished and cautious potentates of American Jewry, including Louis D. Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter, and the denizens of established Wall Street banking firms. Among other things, the disputes about Zionism apparently caused Einstein not to be invited to lecture at Harvard and prompted many prominent Manhattan Jews to decline an invitation from him to discuss his pet project, the establishment of a university in Jerusalem [[lxxxiii]].

These tensions almost got Einstein cancelled from the tour before it had begun. The successor of Supreme Court Justice, Louis D. Brandeis (1856–1941) as head of the Zionist Organization of America, Judge Julian Mack (1866–1943) along with Harvard Law Professor (destined to be a future Supreme Court Justice) Felix Frankfurter (1882–1965) telegrammed Weizmann shortly before the party departed for America. They informed Weizmann of Einstein’s attempts to commercialize his visit by requesting pricey lecture fees. This crassness, they feared, would hurt Einstein’s image, and harm the reputation of Jews [[lxxxiv]]. They advised him to leave the scientist behind. Weizmann wisely declined their advice to leave the world’s most famous Jew behind, a decision vindicated by the American public’s enthusiastic response [[lxxxv]].

Brandeis, who was then the honorary president of the Zionist Organization of America, had traveled with Weizmann to Palestine in 1919 and attended a Zionist convention in London in 1920. Brandeis wanted the Zionist cause to focus on direct financial support for Jewish settlers in Palestine. The radical Zionists (mostly Eastern European and Russian Jews) were contemptuous of the assimilationist Jews’ (more establishment American, English, and German Jews) attempts to fit in. The assimilationists were disdainful of the radical Jews’ political activism and trouble-making. Brandeis did not trust the Russian Jews with whom Weizmann associated, and he preferred more efficient managers to take the helm of the Zionist movement.

Writing to his brother in 1921, Brandeis explained:

The Zionist [clash] was inevitable. It was one resulting from differences in standards. The Easterners—like many Russian Jews in this country—don’t know what honesty is & we simply won’t entrust our money to them. Weizmann does know what honesty is—but weakly yields to his numerous Russian associates. Hence the split [[lxxxviii]].

Brandeis wrote to his mother-in-law, “…it is well to remind the Gentile world, when the wave of anti-Semitism is rising, that in the world of thought the conspicuous contributions are being made by Jews” [[lxxxix]]. By focusing the attention on Einstein, the more assimilated Jews of English and German origin diverted attention away from what they regarded as the more radical Zionist movement: a movement much more enthusiastically embraced by their more recently arrived and more activist Eastern European and Russian Jewish brethren.

This was another reason why even Jewish-owned papers might choose to focus on Einstein while downplaying his Zionist mission. The New York Times unleashed a relentless press campaign promoting Einstein with almost daily articles while making the Zionist fundraising mission more of an afterthought.

Rumors that the American Zionists caused Harvard to slight Einstein forced Brandeis’ protégé, Felix Frankfurter, to issue a public denial. This prompted Einstein to reply privately to Frankfurter, arguing that it was “…a Jewish weakness always and eagerly to try to keep the Gentiles in good humor” [[xc]].

After New England, Einstein and his party were off to the Midwest for an exhausting week of lectures and visits to Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin and the University of Chicago. There Einstein gave three lectures and met Robert Andrews Millikan (1868–1953), who would earn the Nobel Prize in 1923 for his work on electrons and the photoelectric effect [[xcii], [xciii]].

In Cleveland, Einstein’s penultimate stop before returning to New York, weeks of relentless media promotion came to a fruition. Jewish businesses closed for the day, thousands greeted the party, and a military band led a parade of two hundred vehicles escorting the party to their hotel. Einstein spoke at the Case School of Applied Science (now Case Western Reserve), home of the famous Michelson-Morley experiment, and met with Dayton Miller, discussing his æther drift experiments for an hour and a half [[xciv], [xcv], [xcvi]].

Einstein had already set sail from New York before the divisions within the American Jewish community came to a climax at the Zionist Organization of America’s annual convention in Cleveland. Weizmann’s faction blocked a vote of confidence endorsing Brandeis and Mack who promptly resigned, causing a deep and long-lasting rift in American Zionism [[xcvii]].

Einstein at Odds with the Zionists

Einstein’s more assimilated Jewish brethren who were annoyed at his behavior and opinions might have taken solace in the fact he was having a similar effect within the more radical wing of the Zionist movement, itself.

Kurt Blumenfeld had warned Weizmann, “As you know, Einstein is no Zionist, and I beg you not to make any attempt to prevail on him to join our organization.... I heard . .. that you expect Einstein to give speeches. Please be quite careful with that. Einstein ... often says things out of naïveté which are unwelcome to us” [[xcviii]].

Einstein preached pacifism wherever he went. He readily agreed to accompany the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann on a fund-raising trip to America but nevertheless annoyed him by complaining that the Zionists were overly militant and should make peace with their Arab neighbors [[xcix]].

Einstein favored what would now be called a two-state solution to the problem of Palestinian-Jewish relations.

Einstein complained that the Zionists were not doing enough to reach agreement with the Palestinian Arabs. Peace and cooperation between Arabs and Jews was not England's problem (Palestine was under British rule) “but our own.” He favored a binational solution in Palestine and warned Chaim Weizmann against “a nationalism à la prussienne” [a Prussian nationalism]. Multinational Switzerland represented a ‘higher stage of political development than any other nation state,’ Einstein said. Weizmann called Einstein a prima donna about to lose her voice [[c]].

“Should we be unable to find a way to honest cooperation and honest pacts with the Arabs,” Einstein wrote Weizmann in 1929, “then we have learned absolutely nothing during our 2,000 years of suffering” [[ci]]. In 1948, Einstein was a co-signer to an open letter criticizing the Herut Movement, the major conservative nationalist political party in Israel from 1948 until its formal merger into Likud in 1988. Herut was “a political party closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties. It was formed out of the membership and following of the former Irgun Zvai Leumi, a terrorist, right-wing, chauvinist organization in Palestine,” the 1948 letter declared [[cii]]. According to some modern definitions of the term, Albert Einstein and his co-signers could be called “antisemitic” for expressing such strong opinions about the predecessor to the present-day ruling party in Israel [[ciii], [civ]]. This is particularly ironic since Einstein was offered the ceremonial position of President of Israel after the previous occupant of the office, Weizmann, died in 1952 [[cv]].

Such concerns were in the distant future, however. Yiddishes Tageblatt, the first successful Yiddish daily in the United States, and a paper known for its conservative and Orthodox stance, editorialized on the occasion of Einstein’s departure. The paper summed up the attitude of the Jewish community:

…Einstein captured the Americans not only with his head, but with his heart. Americans found him not to be a dry and threatening scholar, but a friendly, lively, simple man. He’s a man that does not have the customary arrogance of many of the celebrated, and he’s not capricious towards others as are many intellectuals.

The Jews of America are especially happy with Einstein's visit, because he is the first Jewish celebrity, who is known to the outside world, who came here on a special Jewish mission [[cvi]].

A Stop in England

On the way back to Europe, Einstein and his wife stopped in England. Einstein gave a lecture to an audience of 1000 at the University of Manchester, where he received an honorary degree, before continuing on to London [[cvii]]. There, the Einsteins were the guests of politician and Germanophile Lord Richard Haldane (1856–1928), whose daughter fainted from excitement the first time the distinguished visitor entered the house [[cviii]]. Haldane (uncle to J.B.S. Haldane (1892–1964), the biologist) was the author of the popular book The Reign of Relativity, and was eager to end the divisions of the recent war. Einstein went straight from the train to a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society.

That evening, Haldane hosted a dinner, introducing Einstein to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Thomas Davidson (1848–1930), Harold Laski (1893–1950) of the London School of Economics, George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882–1944) of 1919 eclipse fame, mathematician and philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), J. J. Thomson (1856–1940), and many other distinguished guests [[cx], [cxi]]. The weekend was more relaxed, but included a dinner with Lord Rothschild (1868–1937) (of Balfour Declaration fame) [[cxii]].

On Monday, Einstein paid tribute to Newton by laying a wreath on Newton’s grave in Westminster Abbey [[cxiii]], making a good impression on his English hosts [[cxiv]]. “He came, he saw, he conquered,” declared the Daily Mail [[cxv]].

Aftermath and Implications

“I had to let myself be exhibited like a prize ox,” Einstein declared, but the tour collected $750,000 (equivalent to $13.2M today). This disappointed Weizmann who’d hoped for more [[cxvi]]. “The University seems financially assured,” Einstein wrote to Ehrenfest [[cxvii]]. Einstein elaborated:

I am glad that I accepted Weizmann’s invitation. In many quarters there seems to be a very intense Jewish nationalism which threatens to blossom into impatience and narrow-mindedness, but let us hope that this is only a childish ailment. My journey also did a great deal of good as regards the resumption of international relationships between scientists [[cxviii]].

Einstein did put his foot in his mouth with unguarded remarks to a Dutch reporter, mocking Americans about their enthusiasm over a scientist whose work they did not understand and claiming American men were “the toy dogs of their women” [[cxix]].

Overall, however, the trip cemented Einstein’s American reputation. Bernays’ comments on the influence of Italian opera singer, Enrico Caruso (1873–1921) on music in America could as easily apply to Einstein’s influence on science.

The influence of Caruso on America cannot be measured accurately. Historically, it was like that of all great men who stimulate change. They make their appearance, the time is ripe and the public responds; then the engines of communication spread the news of change. The public gains new standards and criteria, and the culture pattern is changed. He became the symbol of serious music to millions of Americans and gave it greater significance. His publicity breakthrough hastened the acceptance and spread of classical music in all its forms. Newspapers had given musical artists space before, but Caruso made artists more newsworthy. He stepped out of the music page and was front-page news wherever he went and whatever he did. A decade later, Lindbergh made a breakthrough that enhanced the newsworthiness of all aviators [[cxx]].

Einstein in particular and relativity in general were an important but small piece of the overall cultural milieu that emerged in the 1920s. New ideas further pummeled the old cultural order, still reeling from the devastation of the World War. A cult of “science” stepped up and took its place. The effect of science on religion in the 1920s was summed at the time up by the prominent liberal pastor, Dr. Henry Emerson Fosdick (1878–1969):

When a prominent scientist comes out strongly for religion, all the churches thank Heaven and take courage as though it were the highest possible compliment to God to have Eddington believe in Him. Science has become the arbiter of this generation’s thought, until to call even a prophet and a seer scientific is to cap the climax of praise [[cxxi]].

Science and religion clashed most notably in the summer of 1925. In a sweltering courtroom, famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow (1857–1938) argued with orator and three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925) over the case of John T. Scopes (1900–1970), a high school teacher charged with the crime of teaching the theory of evolution to his students. Scopes was convicted, and the law was upheld, but the defense achieved two of its principal goals:

One was to hold the law up to such ridicule, and so to expose the ignorance of one of its chief advocates, that politicians would be chary of supporting monkey laws elsewhere. The other aim was to get Americans sufficiently interested in evolution to learn something about it… [[cxxiii]]

Opponents of the law like journalist and writer H.L. Mencken (1880–1956) could consider their mission accomplished.

Playwrights Jerome Lawrence (1915–2004) and Robert Edwin Lee (1918–1994) dramatically presented and formalized this narrative of events in the play, Inherit the Wind. Stanley Kramer (1913–2001) adapted the play into a 1960 movie that its message of academic freedom might counter the perceived influence of McCarthyism [[cxxiv]]. Darwin had replaced Genesis in the new secular religion.

From the perspective of popular culture, Sigmund Freud and the science of psychology had taught “that sex is the most important thing in life, that inhibitions are not to be tolerated, that sin is an out-of-date term, that most untoward behavior is the result of complexes acquired at an early age, and that men and women are mere bundles of behavior-patterns, anyhow” [[cxxvi]].

A popular contemporary account explains the pervasiveness of science.

The prestige of science was colossal. The man in the street and the woman in the kitchen, confronted on every hand with new machines and devices which they owed to the laboratory, were ready to believe that science could accomplish almost anything; and they were being deluged with scientific information and theory. The newspapers were giving columns of space to inform (or misinform) them of the latest discoveries: a new dictum from Albert Einstein was now front-page stuff even though practically nobody could understand it.… If some of the scientific and pseudo-scientific principles which lodged themselves in the popular mind contradicted one another, that did not seem to matter...

These supposed scientific truths were taken as proof that no truth was possible.

They believed also, these intellectuals, in scientific truth and the scientific method—and science not only took their God away from them entirely, or reduced Him to a principle of order in the universe or a figment of the mind conjured up to meet a psychological need, but also reduced man… to a creature for whose ideas of right and wrong there was no transcendental authority. No longer was it possible to say with any positiveness, This is right, or, This is wrong… The certainty had departed from life. And what was worse still, it had departed from science itself. In earlier days those who denied the divine order had still been able to rely on a secure order of nature, but now even this was wabbling. Einstein and the quantum theory introduced new uncertainties and new doubts. Nothing, then, was sure; the purpose of life was undiscoverable, the ends of life were less discoverable still; in all this fog there was no solid thing on which a man could lay hold and say, This is real; this will abide [[cxxvii]].

We will soon discuss further how this cultural zeitgeist influenced emerging discoveries in atomic physics as scientists devised the laws and principles of quantum mechanics.

Conclusion

Einstein’s remarkable popularity in America was the result of a confluence of several factors:

A well-organized publicity campaign that followed Bernays’ “events-and-circumstances” model, and might have been coordinated by Bernays, himself.

A fortuitous misunderstanding when crowds who arrived to greet Weizmann and the Zionist party were assumed to have arrived to greet Einstein.

The establishment, more assimilationist Jewish media were motivated to promote Einstein to distract from Weizmann’s more radical Zionist mission with which they disagreed. Secondarily, establishment Jews saw an advantage to be gained by promoting the accomplishments of the world’s most famous Jewish scientist.

Einstein’s charisma, appeal, and quotability made a favorable impression on reporters.

Einstein’s theory of relativity could be interpreted to align with the zeitgeist (the spirit of the times), a modernist cultural tendency to overthrow conventional wisdom and traditional beliefs in objective, absolute scientific truth.

Before becoming indignant at the curious prospect of Albert Einstein being smeared as an antisemite for his political opinions, consider how Einstein treated his professional colleagues who took issue with his theories.

Upon his arrival in America in 1921, Einstein, Weizmann, and their associates gave a lengthy interview with reporters. Reflecting on the recent anti-relativity controversy, Einstein claimed any disagreement with relativity was motivated by either ignorance or antisemitism. Asked upon his arrival about the controversy surrounding relativity, Einstein insisted, “No one of knowledge opposes my theory… Those physicists who do oppose the theory are animated by political motives.” What political motives? “Their attitude is largely due to antisemitism” [[cxxviii]].

What’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, after all.

Einstein’s claim that his scientific critics were motivated by antisemitism would soon become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as those critics began to dismiss Einstein’s ideas as “Jewish physics.” What did Einstein’s critics mean by this term? Are there different styles, traditions, or schools of physics of which “Jewish physics” might be considered one? Or is there only one correct and legitimate way to approach physics? These are the questions we will take up in the following section.

Next time: 5.2.9: What is Meant By “Jewish Physics?”

5.2.9 What Is Meant By "Jewish Physics?"

Ideas some today might consider racist or antisemitic were pervasive among Weimar-era Germans. One very prominent German physicist declared:

Enjoyed the article, but maybe not quite enough to spring for a paid subscription?

Then click on the button below to buy me a coffee. Thanks!

Full Table of Contents [click here]

Follow Online:

You may follow me online in other places as well:

Telegram: 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕔𝕫𝕒𝕣'𝕤 𝔸𝕖𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕥𝕣𝕖𝕒𝕞

Gab: @aetherczar

Twitter: @aetherczar

Amazon: Hans G. Schantz

References

[[i]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 294.

[[ii]] Einstein, Albert, Sidelights on Relativity, New York: Dover Publications, 1983, p. 23. Reprinting a lecture: Ether and the Theory of Relativity, An Address delivered on May 5, 1920, University of Leyden. Note the more typical spelling is “Leiden,” and although originally scheduled for May 5, difficulties in securing the visiting professorship delayed the inaugural lecture until October 27, 1920 (see van Delft’s account).

[[iii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 484.

[[iv]] Bernays, Edward L., Biography of an idea: memoirs of public relations counsel, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965, p. 274. See: https://archive.org/details/biographyofideam00bern/page/226/mode/2up.

[[v]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 289.

[[vi]] President Chaim Weizmann, who was a science professor before becoming Israel's first president. By Government Press Office (Israel), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22807528

[[vii]] “THE GERMAN ZIONIST LEADER BLUMENFELD SPEAKING DURING THE DINNER FOR THE FRIENDS OF THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY IN TEL AVIV.” ארוחת ערב לכבוד ידידי האוניברסיטה העברית שנערכה באולם "אוהל שם" בתל אביב. Israeli government photo in public domain. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:THE_GERMAN_ZIONIST_LEADER_BLUMENFELD_SPEAKING_DURING_THE_DINNER_FOR_THE_FRIENDS_OF_THE_HEBREW_UNIVERSITY_IN_TEL_AVIV._%D7%90%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%97%D7%AA_%D7%A2%D7%A8%D7%91_%D7%9C%D7%9B%D7%91%D7%95%D7%93_%D7%99%D7%93%D7%99%D7%93%D7%99_%D7%94%D7%90%D7%95%D7%A0%D7%99%D7%91%D7%A8%D7%A1%D7%99%D7%98.jpg

[[viii]] Singer, Saul Jay, “The Inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem,” December 30, 2020. See: https://www.cfhu.org/news/looking-back-the-inauguration-of-the-hebrew-university-of-jerusalem/#

[[ix]] Sampter, Jessie E., A Guide to Zionism, New York: Zionist Organization of America, 1920, p. 211.

A Hebrew university at Jerusalem had been dreamed of and written of for many years. Just before the war, in 1913, the eleventh Zionist Congress brought that dream near realization. Through the efforts of Dr. Weizmann, Ussischkin and others, a large fund was raised, ground was given for the building on Mount Scopus, near the Mount of Olives, overlooking Jerusalem and the Jordan valley, and much preparatory work was done. The Hebrew University has come to be almost a symbol of Jewish renationalization, of spiritual rebirth. It stands as the spiritual rallying point of Israel. Chaim Weizmann proclaimed that to all the world by making one of his first political acts in Palestine, on July 24, 1918, the laying of the corner-stone of the Hebrew University.

[[x]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 221.

[[xi]] Sampter, Jessie E., A Guide to Zionism, New York: Zionist Organization of America, 1920, p. 85.

[[xii]] Sampter, Jessie E., A Guide to Zionism, New York: Zionist Organization of America, 1920, p. 88.

[[xiii]] “Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Chaim Weizmann in July 1918, the public university officially opened on 1 April 1925.” See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hebrew_University_of_Jerusalem.

[[xiv]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 315.

[[xv]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, pp. 491-497.

[[xvi]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 239.

[[xvii]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 290.

[[xviii]] Chemist Fritz Haber, published in 1919 in Sweden in Les Prix Nobel 1918 (p. 120). Source : http://nobelprize.org/chemistry/laureates/1918/index.html See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fritz_Haber.png

[[xix]] By Unknown (Mondadori Publishers) - http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/portrait-of-the-german-chemist-and-physicist-walter-hermann-news-photo/141553142, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41260080

[[xx]] Anon., “The Progress of Science: Professor Einstein’s Visit to the United States,” The Scientific Monthly, vol. 12, May, 1921, pp. 482-485. See: https://archive.org/details/scientificmonthl12ameruoft/page/482/mode/2up?view=theater

[[xxi]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 290.

[[xxii]] Elon, Amos, The pity of it all: a portrait of the German-Jewish epoch, 1743-1933, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003, p. 317.

[[xxiii]] Elon, Amos, The pity of it all: a portrait of the German-Jewish epoch, 1743-1933, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003, pp. 276-277.

[[xxiv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 291.

[[xxv]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 496.

[[xxvi]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 497.

[[xxvii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 493.

[[xxviii]] Seelig, Carl, Albert Einstein: A Documentary Biography, translated by Mervyn Savill, London: Staple Press Limited, 1956, p. 143.

[[xxix]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 239.

[[xxx]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 462.

[[xxxi]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 495.

[[xxxii]] Photograph of participants of the first Solvay Conference, in 1911, Brussels, Belgium. Seated (L-R): Walther Nernst, Hendrik Lorentz, Ernest Solvay (he wasn’t present when the above group photo was taken; his portrait was crudely pasted on before the picture was released), Marcel Brillouin, Emil Warburg, Jean Baptiste Perrin, Wilhelm Wien, Marie Skłodowska-Curie, and Henri Poincaré. Standing (L-R): Robert Goldschmidt, Max Planck, Heinrich Rubens, Arnold Sommerfeld, Frederick Lindemann, Maurice de Broglie, Martin Knudsen, Friedrich Hasenöhrl, Georges Hostelet, Edouard Herzen, James Hopwood Jeans, Ernest Rutherford, Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, Albert Einstein, and Paul Langevin. See: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ca/1911_Solvay_conference.jpg

[[xxxiii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 80-81.

[[xxxiv]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 495.

[[xxxv]] Gimbel, Steven, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 8.

[[xxxvi]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 496.

[[xxxvii]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 314.

[[xxxviii]] ALBERT EINSTEIN (1879-1955) German-American theoretical physicist is welcomed on his first visit to New York in 1921. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo. Licensed use from Alamy; note that this is probably a public domain photo, but first publication before 1929 or so would have to be established. See: https://www.alamy.com/albert-einstein-1879-1955-german-american-theoretical-physicist-is-image66530751.html. See also: https://infogalactic.com/info/File:Einstein_in_NY_1921.jpg

[[xxxix]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 292.

[[xl]] Falk, Dan, “One Hundred Years Ago, Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity Baffled the Press and the Public: Few people claimed to fully understand it, but the esoteric theory still managed to spark the public’s imagination,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 4, 2019. See: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/one-hundred-years-ago-einsteins-theory-relativity-baffled-press-public-180973427/

[[xli]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America’s Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://archive.is/Wl1kz

[[xlii]] Albert Einstein and leaders of the World Zionist Organization published in the USA in 1921. Also pictured are Chaim Weizmann, [Menachem Ussishkin and Ben-Zion Mossinson (headmaster of the Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium), cropped] onboard SS Rotterdam (1908), 2 April 1921. “Professor Einstein's Visit to the United States,” Bain News Service, publisher - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ggbain.32100. See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albert_Einstein_WZO_photo_1921_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:Einstein_Apr.1921_SS_Rotterdam_32100.jpg

[[xliii]] Missner, Marshall, “Why Einstein Became Famous in America,” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 15, No. 2, May, 1985, pp. 267-291. See: https://www.jstor.org/stable/285389

[[xliv]] Bragdon, Trevor, “Albert Einstein’s Mistaken Identity,” Pitch & Persuade Substack, May 7, 2022. See: https://www.trevorbragdon.com/cp/156518205

[[xlv]] Missner, Marshall, “Why Einstein Became Famous in America,” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 15, No. 2, May, 1985, pp. 267-291. See: https://www.jstor.org/stable/285389

[[xlvi]] Missner, Marshall, “Why Einstein Became Famous in America,” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 15, No. 2, May, 1985, pp. 267-291. See: https://www.jstor.org/stable/285389

[[xlvii]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America’s Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://archive.is/Wl1kz

[[xlviii]] Coleman, John, CONSPIRATORS' HIERARCHY: THE STORY OF THE COMMITTEE OF 300, November 7, 1991. See: https://archive.org/details/conspirators-hierarchy-the-story-of-the-committee-of-300-dr.-john-coleman/page/n55/mode/2up

[[xlix]] O’Carroll, Patrick, “Hey, Hey, We’re the Beatles,” James Perloff [blog], July 28, 2023. See: https://jamesperloff.net/hey-hey-were-the-beatles/ or https://archive.is/EnNtu. For a countervaillingview, see Klee, Miles, “The Beatles Are the Perfect Band for QAnon Believers,” Rolling Stone, December 7, 2022. See: https://archive.is/PDPG1

[[l]] Jeff Jacoby, “The Public Be Swayed: Edward Bernays, the ‘Father of Public Relations,’ Is Still Giving Advice on His 100th Birthday,” The Jerusalem Report, February 13, 1992. See: https://jeffjacoby.com/5708/the-public-be-swayed.

“IN HIS HEYDAY, they all came to Edward Bernays: Henry Ford, Enrico Caruso, Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes. He counseled Chaim Weizmann in the 1920s and Jawaharlal Nehru in the 1940s. He accompanied the American delegation to the Paris peace talks after World War I, and found an American publisher for his uncle, Sigmund Freud. From the electric light bulb to the American civil rights movement, Bernays was always called in -- to promote the product, enhance the image, win the favorable press notices.”

[[li]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, p. 96. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lii]] Bernays, Edward L., Biography of an idea: memoirs of public relations counsel, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965, p. 222. See: https://archive.org/details/biographyofideam00bern/page/226/mode/2up.

[[liii]] Bernays, Edward L., Biography of an idea: memoirs of public relations counsel, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965, pp. 701-704. See: https://archive.org/details/biographyofideam00bern/page/226/mode/2up.

[[liv]] Jeff Jacoby, “The Public Be Swayed: Edward Bernays, the ‘Father of Public Relations,’ Is Still Giving Advice on His 100th Birthday,” The Jerusalem Report, February 13, 1992. See: https://jeffjacoby.com/5708/the-public-be-swayed.

[[lv]] Bakis, Kirsten, “Writing Into Negative Space: Shining a Spotlight on History’s Sidelined Women,” Literary Hub, February, 21, 2024, See: https://lithub.com/writing-into-negative-space-shining-a-spotlight-on-historys-sidelined-women/

“Fort did not easily find the financial security he wanted. He got a novel published but it didn’t do very well, and when he attempted to interest editors in his new manuscripts, no one bit. Finally Dreiser, convinced of the importance of the work, cornered his own publisher, Boni & Liveright, home to the likes of Faulkner and Hemingway, threatening to leave unless they took on Fort’s 1919 The Book of the Damned.

“Unwilling to lose Dreiser, they reluctantly produced 500 copies. But their publicist, pioneering propagandist Edward Bernays, gamely offered this selling point in early ads: “For Every Five People Who Read It Four Will Go Insane!”

“I don’t know whether anyone lost their mind from reading his books, but they did often have strong reactions. In later years, when Dreiser sent Fort’s work to H.G. Wells, Wells replied that Charles was “one of the most damnable bores who ever cut scraps from out-of-the-way newspapers. And he writes like a drunkard,” he added, before noting that he tossed the book into the trash.”

[[lvi]] Bakis, Kirsten, Op. Cit.

[[lvii]] Bernays, Edward L., Biography of an idea: memoirs of public relations counsel, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965, p. 283. See: https://archive.org/details/biographyofideam00bern/page/282/mode/2up

[[lviii]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, pp. 10-11. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lix]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, p. 12. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lx]] Bernays, Edward L., Biography of an idea: memoirs of public relations counsel, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965, p. 58. See: https://archive.org/details/biographyofideam00bern/page/282/mode/2up

[[lxi]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, p. 11. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lxii]] Cutlip, Scott M., The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1994, p. 224. Citing a November 1983 interview with Clayton Haswell of the AP.

[[lxiii]] Cutlip, Scott M., The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1994, pp. 170-176.

[[lxiv]] Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, holding a cigar. Photographed by his son-in-law, Max Halberstadt, c. 1921. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sigmund_Freud_LIFE.jpg

[[lxv]] Charles Fort, 1920. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Fort#/media/File:Fort_charles_1920.jpg

[[lxvi]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, p. 96. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lxvii]] Cutlip, Scott M., The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1994, p. 203.

[[lxviii]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, p. 138. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lxix]] Cutlip, Scott M., The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1994, p. 125.

[[lxx]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, p. 117. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lxxi]] Cutlip, Scott M., The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1994, p. 190.

[[lxxii]] Tye, Larry, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & the Birth of Public Relations, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, p. 117. See: https://dokumen.pub/the-father-of-spin-edward-l-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-9780805067897-0805067892-2001024223-g-6212205.html.

[[lxxiii]] See: https://books.google.com/books?id=jS5eAAAAIBAJ&lpg=PA18&dq=einstein&pg=PA18#v=onepage&q=einstein&f=false

[[lxxiv]] Anon., “Professor Einstein Here, Explains Relativity,” New York Times, April 3, 1921.

[[lxxv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 295.

[[lxxvi]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 297.

[[lxxvii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 265.

[[lxxviii]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America's Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/12/how-einstein-divided-americas-jews/307763/

[[lxxix]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 297.

[[lxxx]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 503.

[[lxxxi]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 113.

[[lxxxii]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 265. Pais was born and raised in the Netherlands, so I’m not sure this is a fair criticism.

[[lxxxiii]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America's Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/12/how-einstein-divided-americas-jews/307763/

[[lxxxiv]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America's Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/12/how-einstein-divided-americas-jews/307763/

[[lxxxv]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 499.

[[lxxxvi]] A 1916 photo of Louis Brandeis. Harris & Ewing - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ppmsca.06024. Public Domain. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Brandeis#/media/File:Brandeisl.jpg

[[lxxxvii]] A 1939 photo of Felix Frankfurter. By Harris & Ewing, photographer - |source=Library of CongressCatalog: https://lccn.loc.gov/2016862746Image download: https://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/hec/21700/21701v.jpgOriginal url: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016862746/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=152557903

[[lxxxviii]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America's Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/12/how-einstein-divided-americas-jews/307763/

[[lxxxix]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America's Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/12/how-einstein-divided-americas-jews/307763/

[[xc]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 298.

[[xci]] Millikan and Albert Einstein at the California Institute of Technology in 1932. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Andrews_Millikan#/media/File:Millikan_and_Einstein_1932.png

[[xcii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 503.

[[xciii]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 299.

[[xciv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 300.

[[xcv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 300.

[[xcvi]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 113.

[[xcvii]] Isaacson, Walter, “How Einstein Divided America's Jews,” The Atlantic, December 2009. See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/12/how-einstein-divided-americas-jews/307763/

[[xcviii]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 315.

[[xcix]] Elon, Amos, The pity of it all: a portrait of the German-Jewish epoch, 1743-1933, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003, p. 361.

[[c]] Elon, Amos, The pity of it all: a portrait of the German-Jewish epoch, 1743-1933, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003, pp. 379-380.

[[ci]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 381.

[[cii]] Albert Einstein, et al, “Letter to The New York Times: New Palestine Party; Visit of Menachen Begin and Aims of Political Movement Discussed,” New York Times, December 4, 1948. Cosigners included Hannah Arendt, Zelig S. Harris, Sidney Hook, Bruria Kaufman, Irma L. Lindheim, Seymour Melman, and Fritz Rohrlich. See: https://archive.org/details/AlbertEinsteinLetterToTheNewYorkTimes.December41948

[[ciii]] U.S. Department of State, “Defining Antisemitism.” Examples of “antisemitism” include “Drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.” See: https://www.state.gov/defining-antisemitism/

[[civ]] Gordon, Neve, and Mark LeVine, “Was Einstein an Anti-Semite?” Inside Higher Ed, March 26, 2021. See: https://archive.is/kpi1R.

[[cv]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 508.

[[cvi]] Missner, Marshall, “Why Einstein Became Famous in America,” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 15, No. 2, May, 1985, pp. 267-291. See: https://www.jstor.org/stable/285389.

[[cvii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 505-506.

[[cviii]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, pp. 311-312.

[[cix]] From a photo by Walter Benington. Originally published in The Sphere on 18 June 1921, it was later reproduced in Hutchinson’s Splendour of the Heavens (1923). See: https://eclipse1919.org/index.php/the-expeditions/12-einstein-in-england-june-1921

[[cx]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 279.

[[cxi]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 507-508

[[cxii]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 507. I assume this was Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild of Balfour Declaration fame, but Fölsing does not specifiy.

[[cxiii]] Pais, Abraham, ‘Subtle is the Lord…’ The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, pp. 311-312.

[[cxiv]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 507-508. Fölsing says Haldane arranged a dinner with Rayleigh during Einstein's 1921 visit to England, which was quite a feat since Rayleigh died in 1919.

[[cxv]] Wazeck, Milena, Einstein’s Opponents: The Public Controversies about the Theory of Relativity in the 1920s, Cambridge: University Press, 2014, p. 71. “He came, he saw and conquered. He is a German and gives his lectures in the German language, a fact that doesn’t exactly commend him to an English public. He is a Jew. He brings with him a new theory, you might say a fantastic theory, that tosses all previous views out the window, and the scientific, academic world is very conservative, as is well known. He is a revolutionary. And yet, people received him not just kindly, but rather quite enthusiastically. Where does this come from? Because Professor Einstein is a man whose genius is written on his face [...] Whether or not you understand his language is irrelevant. You know that you are under the spell of a captivating personality, an immense intellectual power.”

[[cxvi]] Ohanian, Hans, Einstein’s Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 263

[[cxvii]] Seelig, Carl, Albert Einstein: A Documentary Biography, translated by Mervyn Savill, London: Staple Press Limited, 1956, p. 171

[[cxviii]] Seelig, Carl, Albert Einstein: A Documentary Biography, translated by Mervyn Savill, London: Staple Press Limited, 1956, p. 171

[[cxix]] Fölsing, Albrecht, Albert Einstein, Ewald Oser, translator, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 508-509.

[[cxx]] Bernays, Edward L., Biography of an idea: memoirs of public relations counsel, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965, p. 144. See: https://archive.org/details/biographyofideam00bern/page/226/mode/2up.

[[cxxi]] Allen, Frederick Lewis, Only Yesterday : An Informal History of the Nineteen-Twenties, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1931, p. 199.

[[cxxii]] Photo taken of Clarence Darrow (left) and William Jennings Bryan (right) during the Scopes Trial in 1925. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scopes_trial#/media/File:Scopes_trial.jpg

[[cxxiii]] de Camp, L. Sprague, The Great Monkey Trial, Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Company, 1968, p. 492. See also, Torley, Vincent, “Six bombshells relating to H.L. Mencken and the Scopes Trial, Uncommon Descent, October 24, 2014. See: https://uncommondescent.com/intelligent-design/six-bombshells-relating-to-h-l-mencken-and-the-scopes-trial/

[[cxxiv]] Blankenship, Bill, “Inherit the Controversy: Topeka Civic Theatre to stage ‘Inherit the Wind,’ a 1955 play that used Darwin vs. Genesis as a way to speak out against McCarthyism,” Topeka Capital-Journal, March 2, 2001. See: https://web.archive.org/web/20141113051143/http://cjonline.com/stories/030201/wee_inherit.shtml

[[cxxv]] Metro Goldwyn Mayer (film trailer), Inherit the Wind, 1960. Spencer Tracy as Henry Drummond, Harry Morgan as Judge Mel Coffey, and Fredric March as Matthew Harrison Brady in a trial scene in the 1960 motion picture Inherit the Wind (uncopyrighted movie trailer screenshot). See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Inherit_the_Wind_trial.jpg

[[cxxvi]] Allen, Frederick Lewis, Only Yesterday : An Informal History of the Nineteen-Twenties, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1931, p. 198.

[[cxxvii]] Allen, Frederick Lewis, Only Yesterday : An Informal History of the Nineteen-Twenties, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1931, pp. 240-241.

[[cxxviii]] Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 297.

This is a fascinating read. I'm intrigued by the impact science had on religion. With the popularisation of Darwin's theories, followed by Einstein's relativity and then Freud's ideas, all happening against the backdrop of a world at war, it's no surprise the cultural zeitgeist shifted toward moral relativism. Afterall, if one believes a naturalistic account of origins, and is told that nothing in the physical universe is absolute, it seems like a natural progression to believe that objective truth does not exist.

From this perspective, it’s a positive development that science has been losing some of its authority in recent years. People are recognising that the philosophical foundations of science are quite shaky and need to be transcended by absolute truth.

Scientism and anti-science in 1920! All mixed together for a startling soufflé. The more things change the more they remain the same.

These days we are taught to greatly fear a mild virus (because Science), greatly fear catastrophic CO2 (because Science) but greatly accept a man that says he's a woman. Where'd the Science go?

Sorta like Einstein the 'Anti-Zionist' was the greatest weapon of Zionism. Good cop bad cop? Cowabunga